Such a very small country with outsized influence, wealth and heft, a city in a garden, guarded and outgoing, audacious and cautious, incredibly modern and beautiful, traditional (with a question mark), meticulously well kept, orderly and kempt, vulnerable. Nice place, Singapore.

Weighing in at just under 280 square miles (a quarter the size of Rhode Island), Singapore has maintained very walkable neighborhoods well integrated with new construction, including public housing (in a country where 80% of the population lives in “public housing”), and stitched together with a remarkable public transit system. The answer to “how do I get there” invariably is, “well you could walk,” perhaps in some combination with the MRT (an easy to navigate subway system with nearly island wide coverage).

Having dropped our bags at our hotel in the heart of the colonial district (not far from Raffles Hotel), we headed out on foot for Chinatown.

Sri Mariamman Temple

It may seem odd that the first stop after walking to Chinatown is a Hindu temple, but this is the oldest Hindu temple in Singapore and was founded by Narayan Pillai, who came to Singapore in 1819 with none other than Sir Stamford Raffles who struck a deal with a member of the sultanate of Johor’s royal family to lay claim to the island as a trading post for the East India Company.

Built in 1827, its imposing entrance tower or gopuram is from the 1930s, but it is best known for a fire-walking ceremony.

Buddha Tooth Relic Temple

Just up the road from Sri Mariamman is the Buddha Tooth Relic Temple housing the purported left canine tooth of the Buddha and constructed in 2007. We happened to show up during a service, stayed a few minutes to listen to the singing and moved on.

Gardens by the Bay & Marina Bay Sands

Still getting our hang of Singapore, we took our hotel’s advice and headed off to the Gardens by the Bay by MRT, planning on being there for the evening and gradually working our way home on foot.

First, Singapore does public spaces really well (although the Flower Dome, shown here, and the Cloud Dome charge admission). The huge area covered by the Gardens is quite beautiful and engaging. Even in the shopping malls you don’t mind being five stories under ground.

As night fell, everyone gathered for the sound and light show starring those truly gigantic living gardens, the Supertrees. All were in good humor even though we had to occasionally unfurl our umbrellas.

Some spectators must have felt like they were in the middle of an enormous stage as a very robust sound system brought beautifully romantic opera swirling through the Gardens.

We made our way from the Gardens with throngs of people over the Dragonfly Bridge, enjoying the nighttime scenery . . .

making our way to . . .

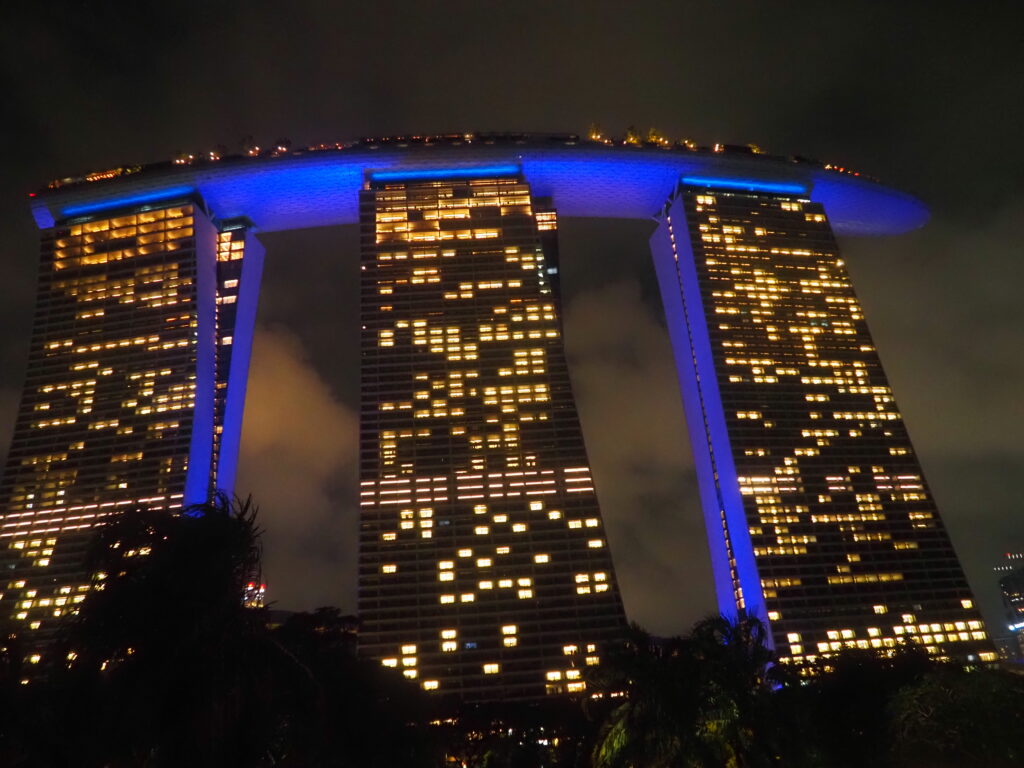

and through the now iconic (since 2010) Marina Bay Sands (featured, of course, in that final scene of Crazy Rich Asians with the giant infinity pool up top) . . .

then over the Helix Bridge to cross the reservoir to the colonial district on the becoming-a-bit-long walk back to our hotel.

Raffles Hotel

Famed for its clientele and invention of the Singapore Sling, as well as its Sikh doormen, the Raffles Hotel was just down the road from our hotel. It has a rather nice gift shop, just like any respectable museum. Tourists are kindly asked to not use the main entrance.

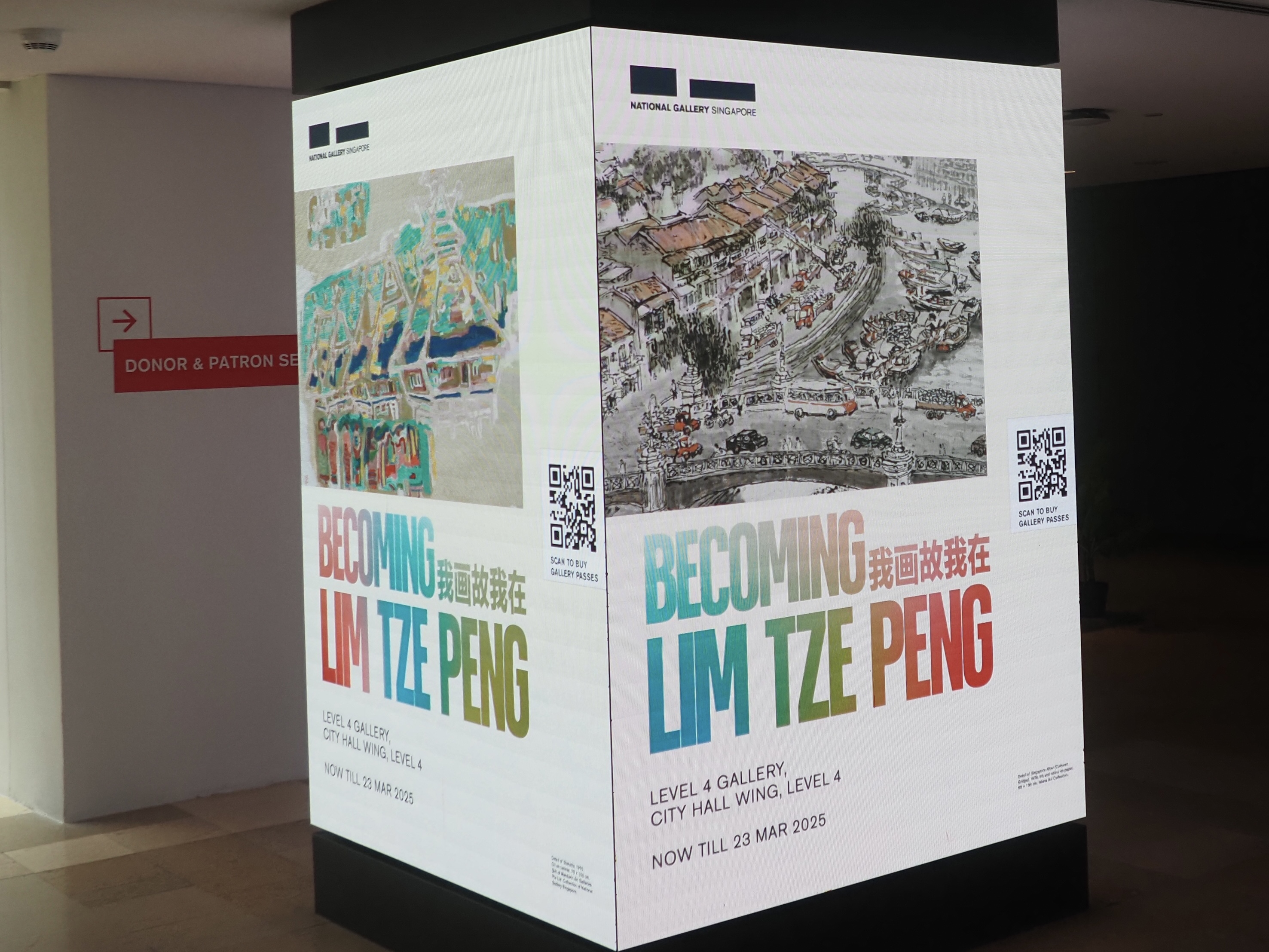

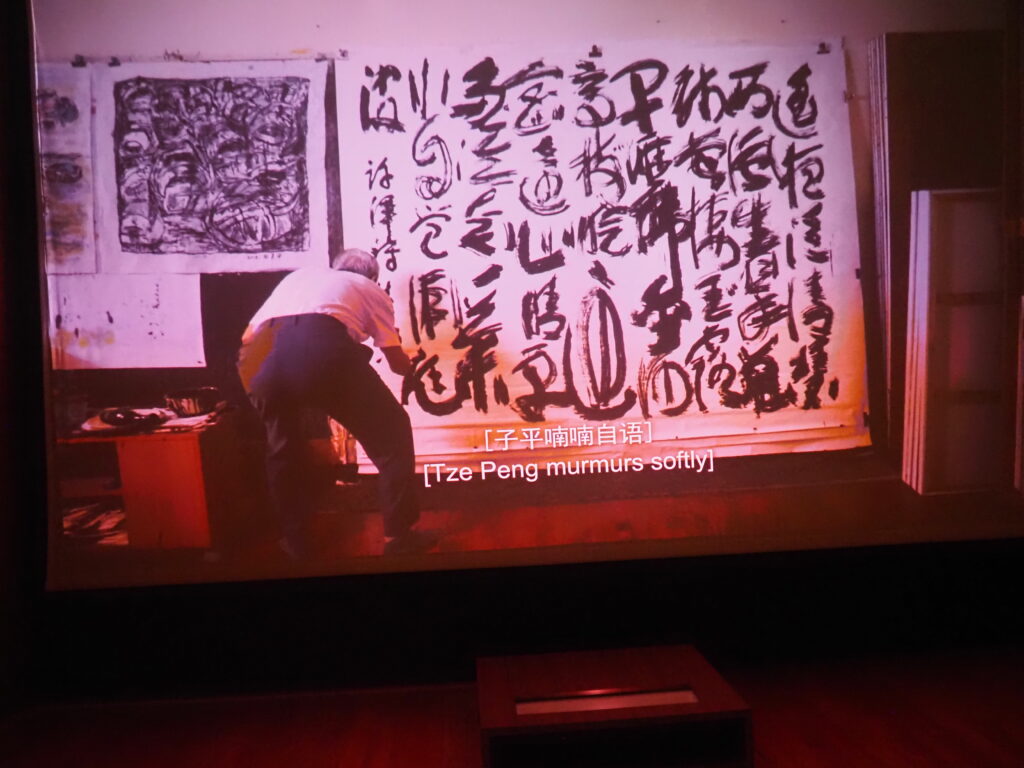

The National Gallery

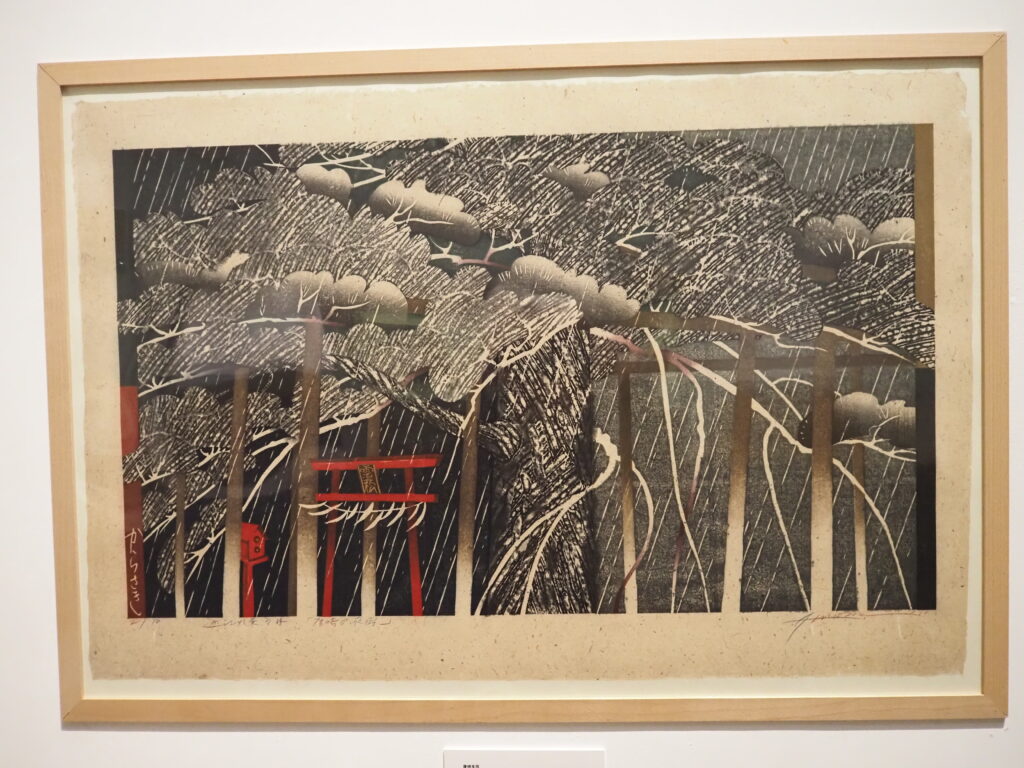

The featured exhibit when we visited The National Gallery was a retrospective of the work of Lim Tze Peng, referred to as the 101 year old artist by the friendly guard who helped us when we couldn’t find our way. Actually Lim is said to have been actively painting in 2021 when he was 99.

In any case, it was nice to see an artist’s range of output over such a long time scale.

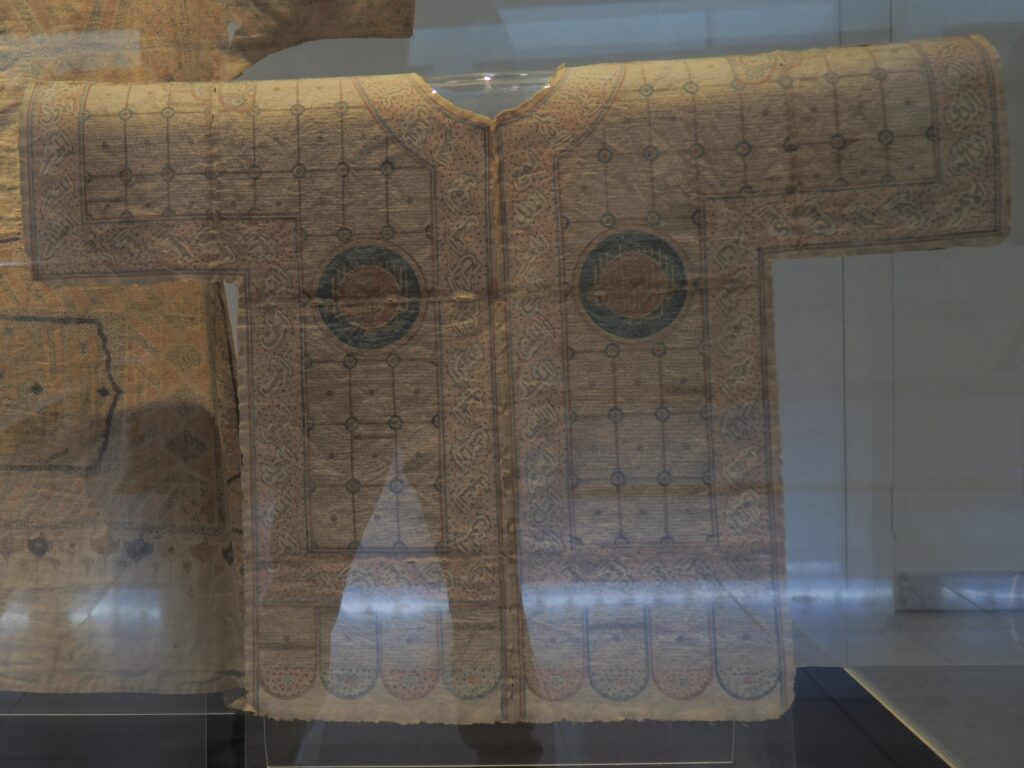

We spent a lot of time in the galleries, become just a little more familiar with the art of the region and enjoying it quite a bit. It was interesting to see how artists in the region were influenced by western artists and visa versa. There seemed to be multiple conversations going on at multiple levels.

The National Gallery, in two adjacent buildings, is connected by an atrium, an out of the way spot to lounge and have a chat.

Around the Corner and Across the Road

Singapore just seems so oddly convenient. Look out a window at the National Gallery and there’s the Marina Bay Sands (that photo way at the top). Exit the main doors and there’s St. Andrew’s Cathedral where they were having some sort of conference with people flooding in (30% of the population happening to be Christian) practically the whole time we were in town (watching the comings and goings from our hotel room across the road).

Then, deep down in the shopping center that somehow seemed hidden away a three minute walk from either the National Gallery or our hotel, well below the street level entrance with bike lanes running through it, was a very well patronized climbing wall, as well as an Indian restaurant we quite enjoyed and where we again indulged in panipuri.

It’s a densely designed city that doesn’t feel that way.

Orchard Road & Emerald Hill Road

Just off Orchard Road, the stretch of opulent shopping that makes you wonder if there are more Gucci stores or 7 Elevens in Singapore, is Emerald Hill Road, a mostly residential, visually beautiful reminder of the colonial past with some Chinese elegance thrown in.

Kampong Glam, Haji Lane & Arab Street

Another walk from the colonial core, this time heading north (Chinatown being south and Orchard Road west), we’re in the traditional Muslim quarter that’s packed with colorful and quirky boutiques and shops of all kinds, especially on Haji Lane.

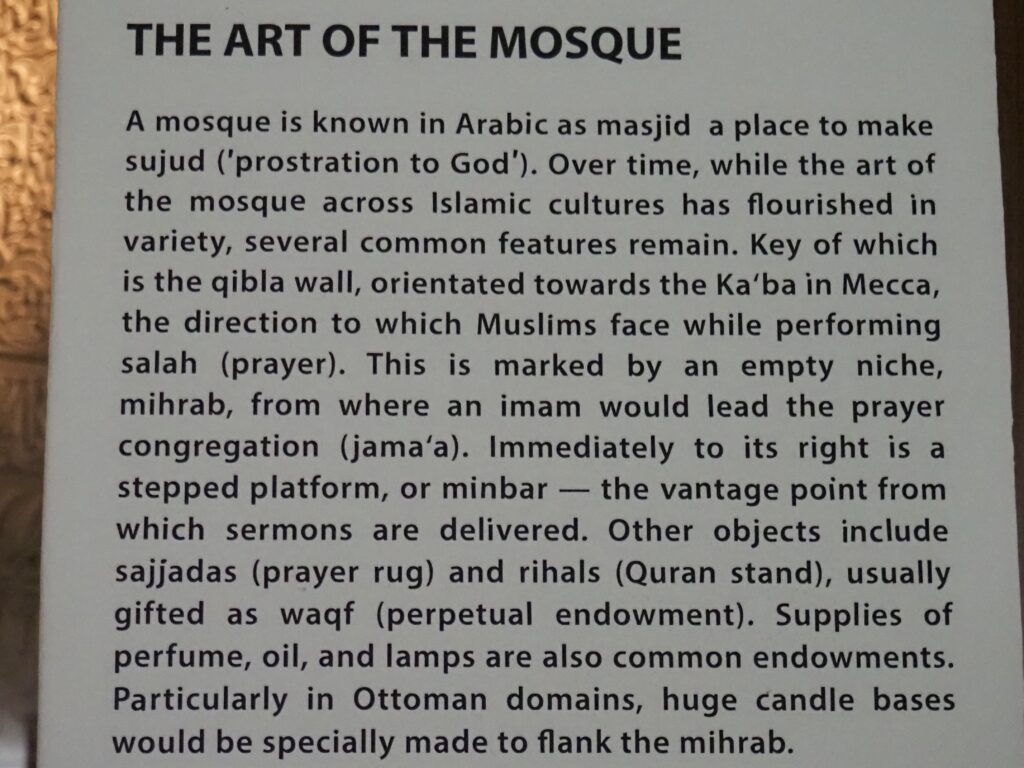

Reputedly Singapore’s grandest mosque (“nothing short of enchanting” our guidebook assures us), we picked the wrong day – Friday – to drop by Masjid Sultan, just off Arab Street, as it was closed to non-Muslims all day.

The neighborhood surrounding the mosque was nonetheless fun to explore.

Little India

A few blocks on foot and we’re in Little India.

From the on-site “heritage trail” signage: “Built in 1900, the former house of Tan Teng Niah is the last surviving Chinese villa in Little India. It embodies an often overlooked story of the days when small Chinese industries operated alongside the cattle and rattan businesses at Little India. Tan Teng Niah was a towkay (Chinese businessman of good standing) who owned several sweet-making factories along Serangoon Road that used sugarcane to produce sweets. Behind the house, Tan had a rubber smoke-house for drying rubber which used the by-products of sugarcane as fuel for its furnace.” The restoration received an architecture award in 1991, although we don’t know if the paint colors and design were faithful to 1900 or a tourism friendly innovation, for it’s the paint job that makes it special.

Little India’s main Hindu temple, Sri Veeramakaliamman is devoted to Veeramakaliamman or the goddess Kali, a fierce incarnation of Shiva’s wife and the Destroyer of Evil, as well as ignorance and disorder in the world. In the 1850s Tamil lime pit workers erected a shrine dedicated to Kali. A temple was then built by Bengali laborers in 1881 and the temple has fallen into disrepair and been rebuilt a number of times, the current temple looking much more prosperous than photos from the 1980s, for instance.

Most temples we visited were alive with activity, people coming to pray with families, with friends, or alone, often with priests helping them with rituals and ceremonies.

Time for Food

There’s again a mixture of the familiar and the not so much.

Of course, there’s a satay and a satay sauce, but also rojak, a salad with pineapple, mango, cucumbers and shrimp paste, quickly an Amanda favorite.

Then there’s a masala thosai, thosai being the equivalent of “dosa”, but closer to the original Tamil word. Masala meaning stuffed with spiced potatoes. Another yum.

A not so enthusiastic thumbs up for the oyster cake, though this is one of only two places remaining in Singapore where you can find them. Not so hard to figure out the reason for declining popularity.

Our guide is choosing ingredients for our next dish, a stir fry with fish cakes, morning glory, and so forth and so on, at a food stall in a coffee shop. Coffee shops are similar to hawker centers, but smaller having perhaps 8-15 food stalls, rather than the up to 80 in a hawker center. Both came to be because the profusion of takeaway food sellers was getting out of control in Singapore and the government was concerned about sanitation and, this being Singapore, the disorderliness of it all. So, they organized the move of the businesses into centralized spaces with proper facilities.

Whatever you want to call these places was fine with us as we enjoyed someone else finding all the good food and bringing it to us. And, actually, having a hot chai in a plastic bag may sound unenlightened, but it’s pretty convenient if you’re on the go (and tastes real good).

As We Wandered

Wandering the streets going from place to place to sample different foods also provides a good opportunity to look around at the street, the gorgeous buildings and also the realities of the city. So, where do people live? As already mentioned, 80% of people live in public housing, so there in those buildings behind or in other buildings scattered through the city (or, country, if you will). We’re told there are the same problems of affordability as we face, scarcity driving real estate prices so that young people have a lot of difficulty acquiring a first home. So, like everywhere, Singapore also has issues still to be solved, including how to reduce its dependence on other nations for practically everything, even the water it drinks.

Before we thanked our food guide and went on our way, she asked the priest at Thekchen Choling if we could step inside, as they were hard at work preparing for an event. It’s a small Tibetan Buddhist temple founded in 2001 that promotes “non-sectarian” Buddhism (and, yes, that’s a photo of the Dalia Lama). We saw but a sliver of what seems to be quite a substantial place, essentially a store front that’s grown to have “over 5,000 devotees” and open 24/7.

Singapore Botanic Gardens

It starts quietly enough, nice paths along ponds with turtles and a monitor lizard opening up to a network of paths leading to various themed garden areas. It ends in sum a stupendous place, for us temperate zone folks a fantasy world where all the exotic plants are growing profusely out there in the open! In February!

That’s not wisteria, it’s orchids. The Gardens are really a wonderland where it’s hard not to take one more photo . . .

. . . and there’s more! Inside greenhouses, the Gardens have even more rare and exotic fare. No wonder this was the only place in Singapore where we noticed cruise ship tour groups. Fortunately, it’s such a vast place that it never seemed crowded.

The only thing we wondered was how expensive it must be to live close to the Gardens in the area where most expatriates make their homes. It would certainly be tempting.

Victoria Theatre and Concert Hall

On our final evening in Singapore we walked over to the Victoria Concert Hall for a performance by the Singapore Symphony, various fanfares featuring the brass section and then Bizet. It was a very nice evening and we enjoyed the performances.

Providing a slight glance back to where we’d been on this month long adventure in four countries, there was a monument commemorating the first time a Thai monarch had ever visited a foreign country – in 1871, although traveling was a lot more difficult in his time.

Finally, we end this posting from Singapore where we began it, with a view of that symbol of the assured and audacious side of Singapore, the Marina Bay Sands. Singapore is certainly a more complex, thoughtful, down to earth and human friendly place than that symbol suggests, but it also is true. On balance, there’s a lot to like.