Month: March 2015

A Writing Lesson

Kanazawa

We were off for a weekend trip to Kanazawa. The train north goes alongside Lake Biwa, the largest lake in Japan, and through the mountains. It’s a city with sprinklers on the main roads to wash away the significant snow falls of winter and a local saying that “even if you forget your lunchbox, don’t forget your umbrella.” We were, in fact, quite lucky because rain had been predicted, but we had none.

Kanazawa Castle is across the road from the Garden. Ishikawa Gate is one of the few remaining original buildings from its 400+ year history.

On the other hand, the Myoryugi Temple or “Ninja” Temple is very well preserved and a hot tourist destination where reservations are required for no-cameras tours by fast-talking (Japanese only) guides who move groups along on the hour-long tours at an impressive pace. That said, seeing the temple was well worth it. It appears to be a two-story building from the outside, but is actually four stories in seven layers. It’s an ingeniously constructed wooden defensive bastion with secret rooms, hidden passageways, traps, and stairs through which to spear intruders (23 rooms, 29 staircases), besides being a continuously functioning place of worship.

In putting together this posting, we saw that we’d neglected to take a photo of the Kanazawa train station and so shamelessly poached this one off of the Internet. The public architecture, especially of train stations, is very nice indeed. In addition to this monumental tori, Kanazawa has a fountain in front of the station that spouts water to indicate the time and spell out messages. It’s a lot of fun and, of course, we were once again a little sad to leave yet another city. Add Kanazawa to the list of those worthy of a return visit. The numbers of foreign visitors, by the way, are likely to increase significantly because Shinkansen service to the city from Tokyo was just begun during our visit to Japan and Kanazawa seems to be the new “hot” destination.

Deterred by Fog & Rain

Naoshima will have to wait for another trip due to another foggy morning. There will always be things that are not quite complete and a visit to Naoshima and the other nearby small islands is a good reason to pay a return visit to Takamatsu and Shikoku. Wanting to stay a bit more dry than our day in Kotohira, we made for Japan’s largest wax museum – Takamatsu Heike Monogatari Wax Museum.

But, the real draw of the museum is a series of dioramas dramatizing the rise and fall of the Heike clan in the 12th century, including depictions of the war between the Heike and and Genji clans. The key battle of the Gempei war was fought nearby, not far from the the Shikoku-mura we visited in Yashima. This photo doesn’t do justice to the posing of the diorama of samurais charging down a hill.

A Climb, a Shrine & Kabuki

For some reason, there seemed to be elderly horses being taken care of at the shrine.

We felt the Asahi-sha was the most interesting building architecturally (if that’s a word).

Another excuse to breath – this one a mythical creature.

Then upward. A total of 1,368 stone steps.

“Only” 785 steps to the main hall.

The percussion musicians are shielded from the audience.

. . . and under the stage the machinery is all there. Here is the turntable mechanism that can be used to rotate a large section of the main stage.

The contraption above the walkway is used for flying scenes. They’re all ready for the next performance. The man at the ticket booth handed Kyle a flyer on our way out.

Ritsurin Garden, Takamatsu

This morning we walked through the fog past trucks lined up ready to load onto the ferry and through crowds of people to the ticket counter to purchase our tickets for Naoshima, the art island. We shouldn’t have been surprised at the news. “Our” boat was still at Naoshima and none of the ferries were going anywhere until after the fog lifted. So, we formulated Plan B, hoping for a decent sailing day tomorrow. We made for Ritsurin Garden.

The first stage of the gardens was constructed as a “strolling garden” in the 1620s by the feudal lord or “daimyo” of Takamatsu Domain. It was expanded over the next hundred years and then served as the Matsudaira family residence until the 1870s when it was opened to the public.

The black pines are especially magnificent and ancient. When we asked our volunteer guide about this one, he thought it was probably about 300 years old.

The crane and tortoise pine has been cultivated over hundreds of years with 110 rocks to (if the photo were better) suggest a crane spreading its wings on the back of a tortoise, both symbols of long life. It’s the most prized tree in the garden and is carefully shaped by the head gardener twice a year. A job that takes him two weeks, while other trees command a gardener’s attention for 3 or 4 days.

Another prized specimen is this oak tree that grew up in the decaying trunk of a pine so that when the pine tree finally sloughed away the now-exposed root structure became the trunk of the oak.

The tree on the left is known as the copper tree, being a graft of a black pine (man tree) on the right and a red pine (woman tree) on the left. The needles of a black pine are considerably tougher than those of the red pine, although that has nothing to do with the toughness of the plant, as the red pine has thrived much more in this pairing. Our guide had a good laugh.

Rocks feature prominently in the garden and are highly valued. Some were extravagant gifts to the daimyo. One that was not in a very photogenic setting was brought all the way from Korea and was huge.

An artificial waterfall was constructed opposite one of the tea houses so that guests might enjoy the pleasant sound.

These trees were brought from Okinawa, but grow much larger in Takamatsu because they keep being ravaged by typhoons on Okinawa.

A potted bonsai tree when given as a gift in 1833.

Nagasaki

Nagasaki has a lot to offer for a small city. Perhaps that’s why it seemed to be full of Japanese tourists, clutching their one day passes, just as uncertain about the streetcar route as we were.

Dejima had been an artificial island ordered constructed just off Nagasaki in 1634 by Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu to isolate foreigners, specifically the merchants and seamen facilitating the trickle of foreign trade. (You may remember Tokugawa from some of our postings in 2013.) Initially it was the Portuguese, then the Dutch, who inhabited the island for a rent of roughly $1 million a year. When Napoleon swept into the Netherlands and the Dutch lost their overseas possessions to Britain, Dejima became the only place in the world where the Dutch flag flew from 1811 through 1814.

There are many attractive exhibits and signage in English is very good. This tiny European outpost played an outsized role in the opening of Japan to the technologies and cultures of the outside world. These are some of the plants introduced from Europe.

Still an island is Hashima, uninhabited until 1810 when coal was discovered and the island began to be developed, and better known to the Japanese as Gunkanshima or “Battleship Island.”

Saga & the Yoshinogari Historical Park

Asian Art Museum, Fukuoka

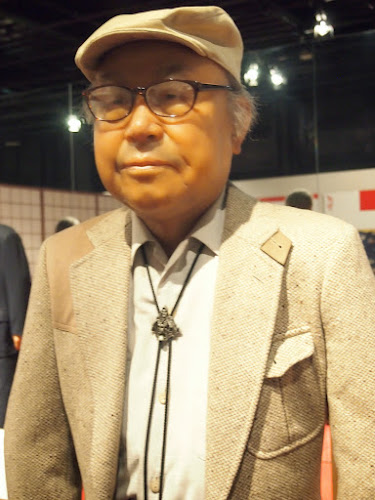

Fukuoka – as the gateway to Kyushu – is also a gateway to Asia for Japan, with important connections by sea. The Asian Art Museum is dedicated to the art of contemporary Asia. We were drawn to the works we wouldn’t equally expect to see in Berlin or New York. To us, they were the most interesting and appealing.

Otaimatsu at Nara

The Temple precinct of Nara feels like the ancient capital it is, well-worn and burnished by time. Up a slope within the Temple complex is Nigatsudo Hall.

We came to experience a unique Buddhist ceremony. Eleven monks come to stay at the Temple to pray for peace and cleanse the world of sin. Bamboo poles are donated to the temple and the donor’s names are written on them. These poles are then transformed into torches with baskets attached to one end ready to be ignited for the ceremony.

Awaiting the night, people stand or kneel at the foot of the hall in the hope that sparks soon to come will land on them and protect them for the coming year. Upon the conclusion of the festival spring will have arrived. In preparation, workers with water tanks on their backs wet down the sides of the wooden structure and the slope just above the onlookers. Fire has destroyed quite a few temples in Japan, although they are quickly and faithfully rebuilt.

After the ceremony the crowd goes up the steps and into the Hall, looking for bits of ashes to improve their prospects for the year . . .