It’s hard to know where to begin when talking about historic Savannah, with its 22 remaining leafy, residential squares, city park, colorful riverfront, thriving restaurant scene, burgeoning art school and downtown cemetery where Union troops passed the time changing dates on tombstones (significantly older than Bonaventure on the city’s edge). So, we might as well begin with the 19th century City Hall that stares down Bull Street that both separates the Easts and Wests of intersecting streets and threads together one row of city squares culminating at Forsyth Park.

the squares

Every square has at least one – and typically several – monument(s) and then a plaque (or plaques), to different people or events and none of them seem to match up with the name of the square, rendering conscientious sign readers both confused and exhausted, effectively curing them of the habit.

It was hard to keep all the squares straight and it was the buildings that began to be our key to navigation.

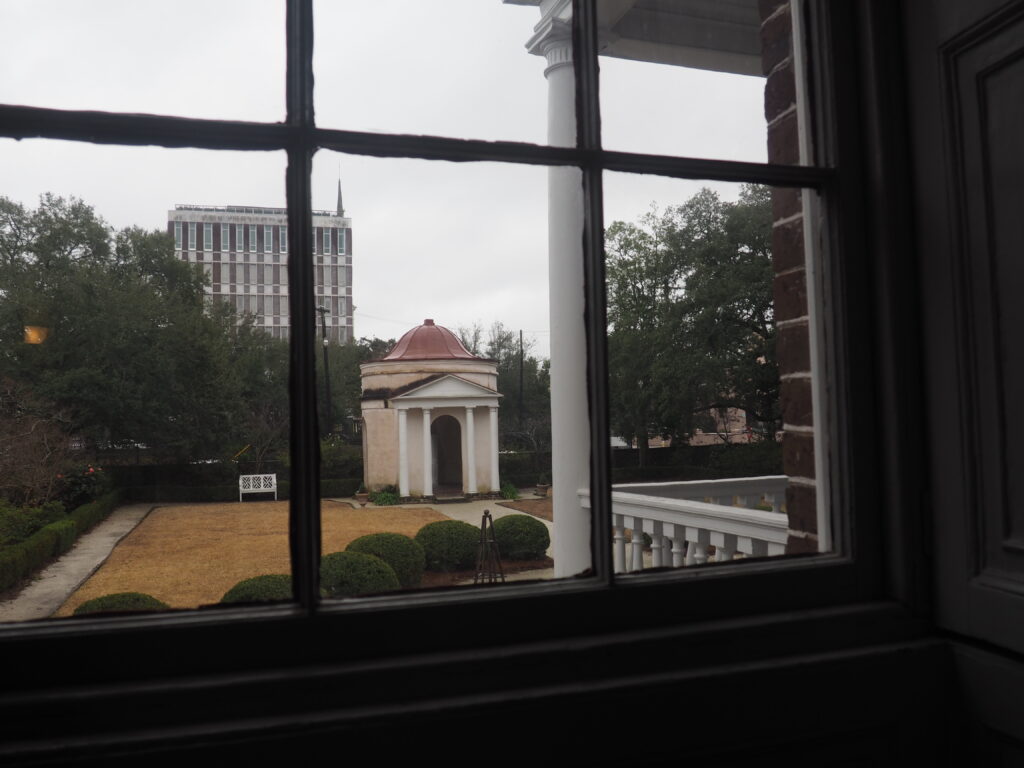

Forsyth park

Forsyth Park was filled with people enjoying themselves eating, drinking, buying things and playing Ultimate Frisbee. Now at the bottom of the pattern of squares, we headed back towards the Savannah River to visit some of the historic homes and institutions.

Taylor square

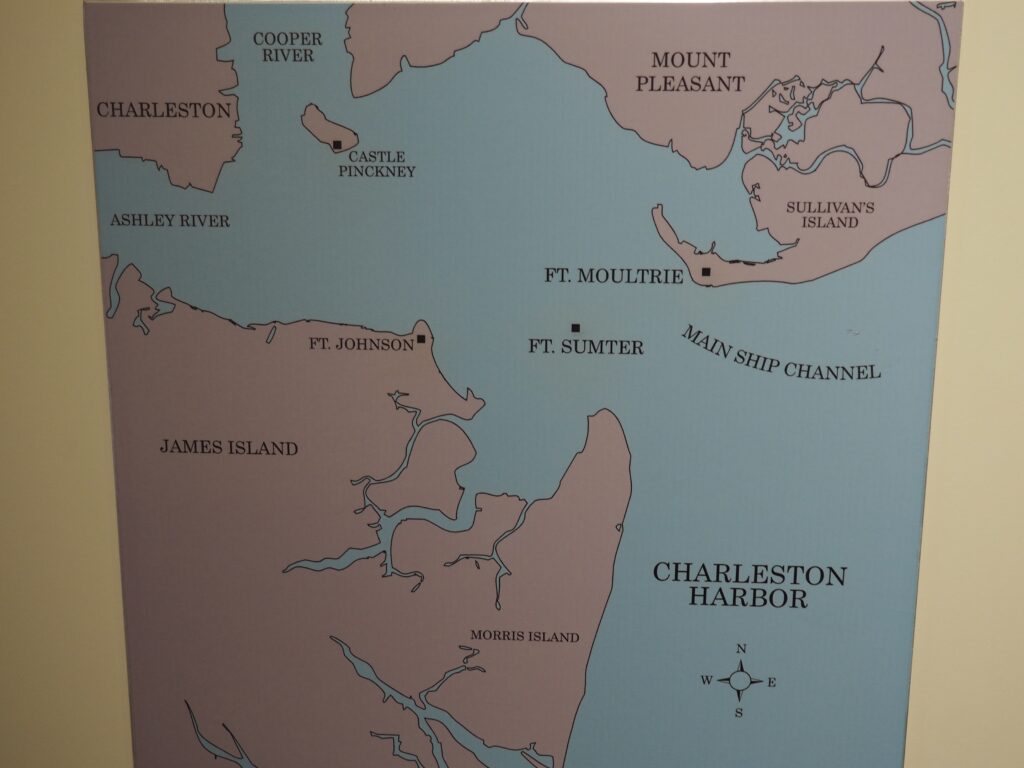

Crossing Taylor Square on our way to the Massie Heritage Center, we came across a performance by the McIntosh County Shouters, a well known Gullah family-based singing group, as part of the celebration of the renaming of Calhoun Square in honor of Susie King Taylor, a teacher and nurse who rose from slavery to play a prominent role in the Civil War around Savannah and in the Sea Islands and to write a memoir about it.

Monterey square

One of those landmarks that help guide your way through Savannah is, of course, the Mercer-Williams House on Monterey Square, one of the squares linked together by Bull Street. It was one of the first houses restored in the 1960s and gained some infamy as the site of the killing at issue in the four murder trials of then owner Jim Williams as recounted in “the book,” i.e. Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil. It’s now a house museum owned and operated by Jim’s sister. It was the only house museum we visited that doesn’t allow photography (and wasn’t a non-profit), although the house was used in the filming of the movie starring Kevin Spacey (who bears a striking resemblance to our main character with the simple addition of a mustache). Bottom line: beautifully restored and furnished with absolutely top notch art and furniture (Williams was an art dealer, after all).

Lafayette square

Andrew Low House, Lafayette Square (1849). Photo Credit: Andrew Low House

Almost by definition, a house museum is going to be spectacular and, since Andrew Low II was a cotton merchant and reportedly the richest man in Savannah, his home (completed in 1849) was definitely not an exception. Touring it on what turned out to be the free-admission Museum Sunday in Savannah, we acquired a timed ticket and returned after seeing a few other, less popular, sites. It turns out that Andrew’s daughter-in-law was none other than Juliet Gordon Low, the founder of the Girl Scouts (who also lived here), married to his somewhat notorious son “Willy.” Perhaps we should just take William Makepeace Thackeray at his word (from 1856): “I write from the most comfortable quarters I have ever had in the United States . . . in the house of my friend, Andrew Low.”

An exception to that rule about house museums always being grand was just across the square at the childhood home of Flannery O’Connor; but writers aren’t expected to live amidst opulence and her father was a mere real estate agent. Dead of lupus by the age of 39 in 1964, this deeply religious Southern Gothic writer of frequently grotesque and disturbing stories had been “well-received,” but achieved fame with the posthumous publication of her Complete Stories. Visiting her childhood home felt to us like visiting the childhood homes of our own parents.

“[A]nything that comes out of the South is going to be called grotesque by the northern reader, unless it is grotesque, in which case it is going to be called realistic.” Flannery O’Connor

Flannery O’Connor attended Mass daily. The truly beautiful Cathedral was on the other side of the Lafayette Square and easy to understand as a source of early inspiration as she later dealt with difficult Catholic themes in her fiction.

Monterey square (again)

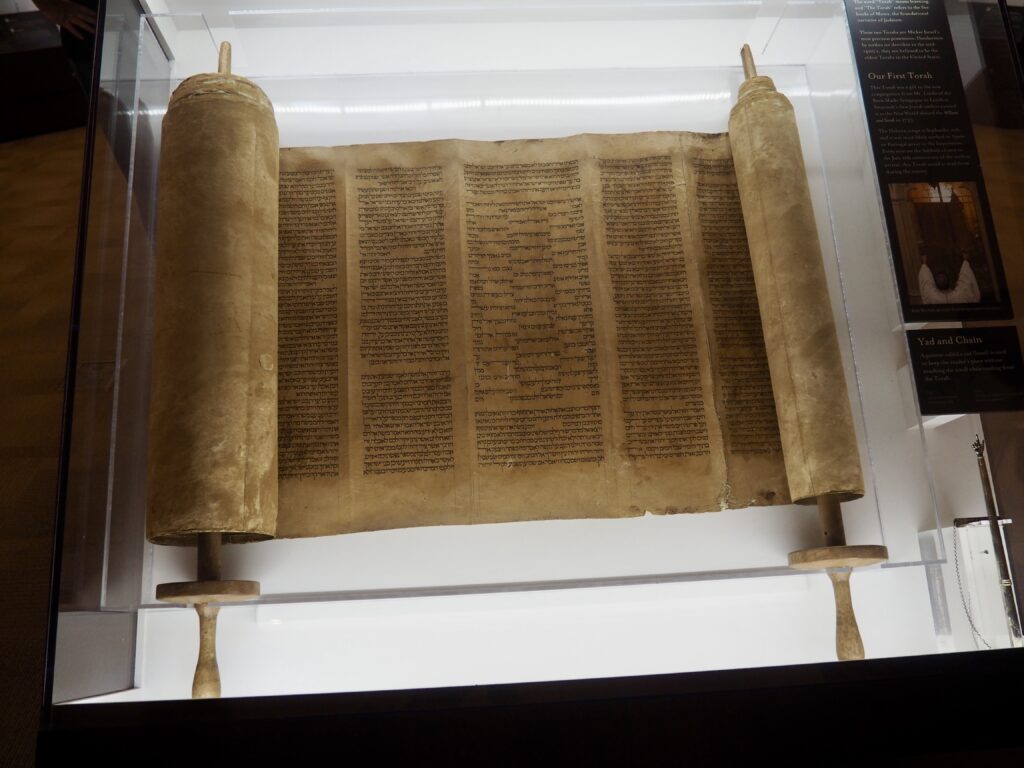

42 English Jews sailed to Savannah in 1733 to participate in the fledgling colony’s experiment in religious tolerance and established the Congregation, the third in America.

When the emigrants were ready to leave in 1733, so the story goes, they asked for one of the Torahs to take with them to America and it was, as always, “Sure, you can take the old one.” It’s the oldest one in America, housed in the only neo-Gothic synagogue in America.

Madison square

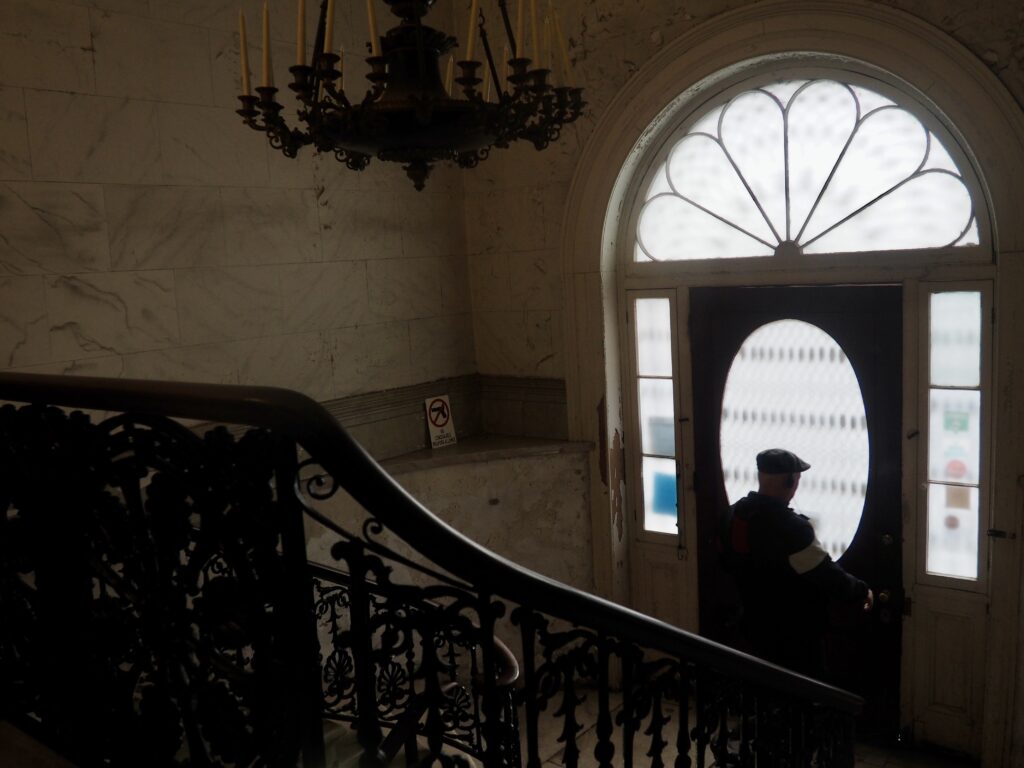

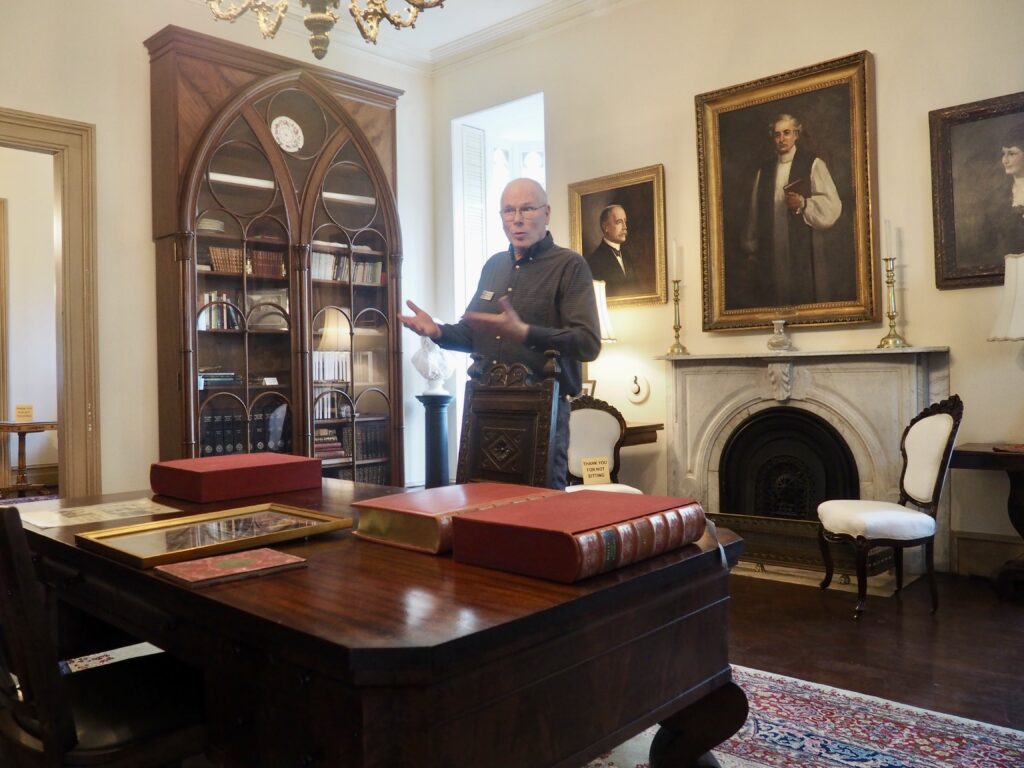

Not particularly wealthy when he arrived in Savannah in 1833, Charles Green built his fortune as a cotton merchant and ship owner and then, as was the case with most of these houses, engaged a New York architect who completed this house in 1850. After inheriting the house, his son Edward sold it to Judge Peter Meldrim whose family sold it to the St. John’s Church next door in 1943 for use as a Rectory and to better assure its preservation.

Among the unusual features of the house is a rather complicated set of front doors where the outer front doors can fold back to create dual entry closets (pretty radical for the time) and two sets of inner front doors slide in or out to provide either glass or louvers, depending on the season.

The ornamental plasterwork was certainly the most extravagant we’ve ever seen. Interestingly, the church does actively use the building for its social functions, while seeming to be good stewards of the house that’s been entrusted to them.

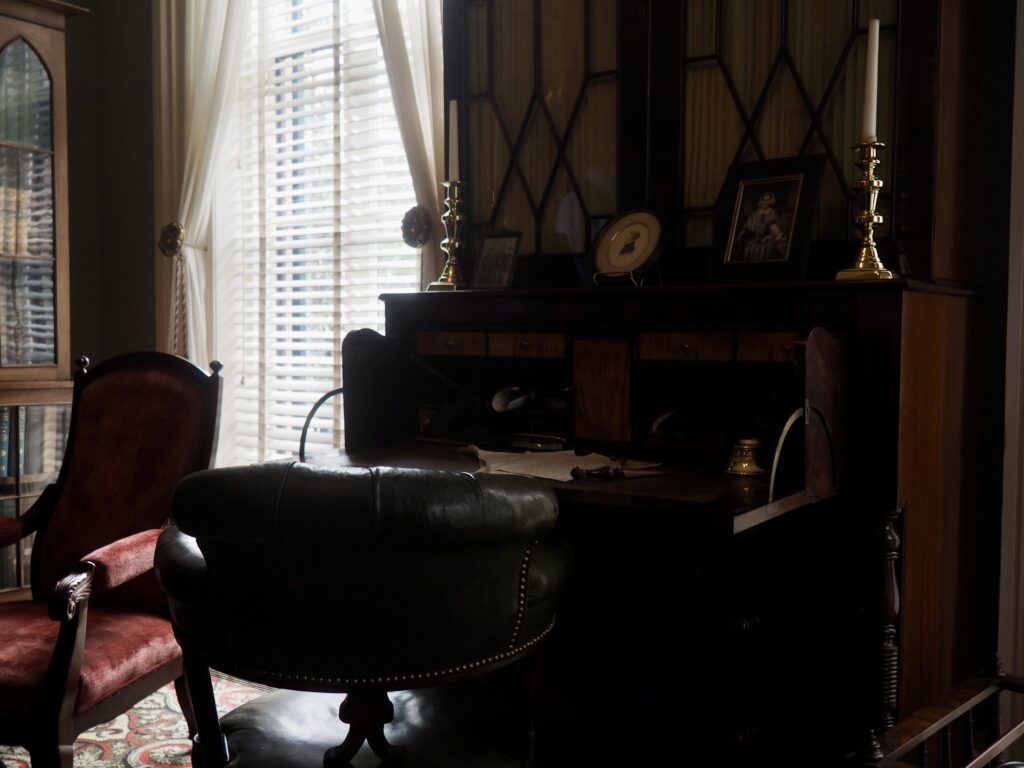

Charles Green, as Mayor of Savannah, had ordered all of the Confederate troops and the police out of the city and issued orders that no one should display a firearm in the city as Sherman’s forces approached. He then invited the General to use his home as his headquarters during the Union occupation of the city. For this the residents considered him to be either a traitor or the hero who had saved Savannah from the fate met by Atlanta to the west. It was from this room that Sherman wrote to Lincoln, making him a Christmas gift of the city of Savannah and issued Field Order #15 granting freed slaves 40 acres of confiscated and abandoned land along the South Carolina, Georgia and northern Florida coasts, along with an army mule to work it, an Order subsequently rescinded by President Johnson. (See also, posting on The Sea Islands)

Oglethorpe square

A Richard Richardson, ship owner and slave owner, built the house but soon suffered both financial and personal reversals, so that it was owned by the Bank of the United States which leased it as a boarding home in 1824 having among its guests the Marquis de Lafayette during his American tour in 1825 to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Revolution. It was then bought by the Owens family in 1830 who ended up bequeathing it to the Telfair Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1951. It’s been a house museum ever since.

The House

The Slave Quarters

along the Savannah river

Along River Street used to be a rough neighborhood, but now is a lot of fun. Lots of restaurants, shops and people.

Our driver Lyle, coming in from the airport after we dropped the car, told us we shouldn’t miss the Marriott’s repurposing of an old power plant along the river and the collection of geodes and other minerals they have on display. He was right. It’s amazing.

adieu, Savannah.

Sorry we couldn’t stay longer.