We started our exploration of historic Charleston at the City Market, a many blocks long brick arcade in the heart of the city, filled with sellers of soaps, hats, hot biscuits, and sweetgrass baskets and children’s duds sold by their makers, and quite busy even on a chilly, cloudy, February Sunday.

Wandering the city, we found the historic center to be a great place to walk and admire the colonial era architecture (especially all those long, side facing porches or “piazzas,” as they say in Charleston) and soak up the atmosphere.

The Nathaniel Russell House (1808)

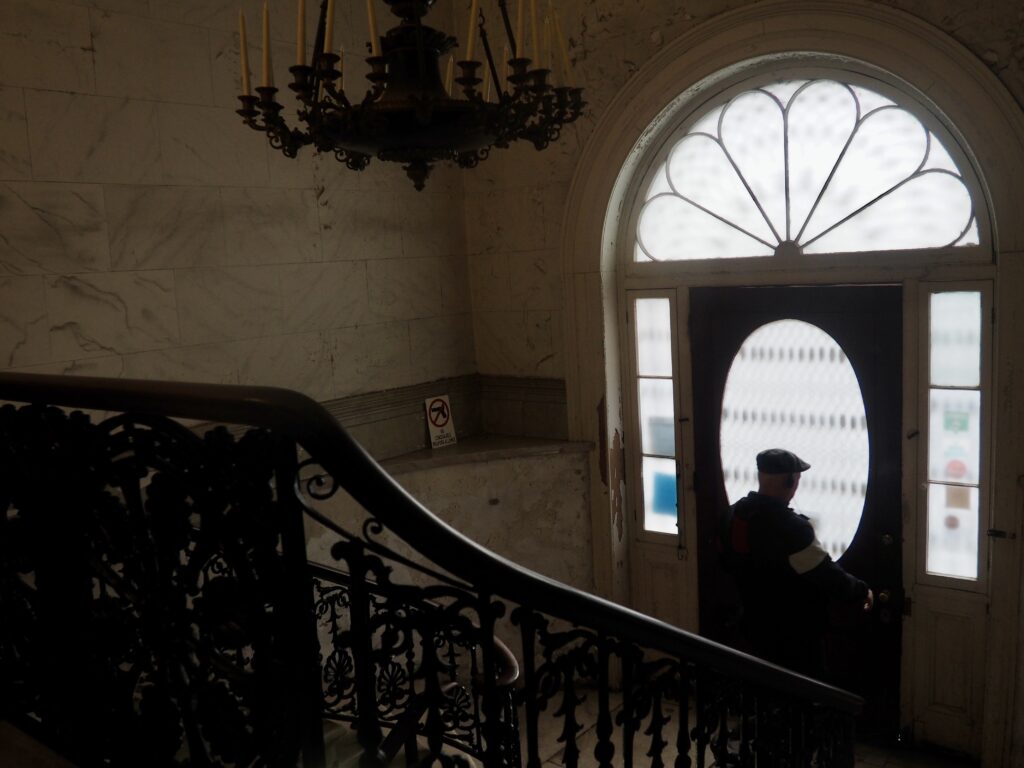

The Nathaniel Russell House was the first of many house museums we visited during our short tour through some of coastal South Carolina and Georgia and, as you can see, its restored elegance and opulence was jaw dropping, especially the three-story, cantilevered, “flying staircase,” helping us to understand the lifestyle a slave economy created for those at the top. Russell was a prominent merchant and slave trader who had come down from Rhode Island before the Revolution.

The Joseph manigault house (1803)

Photo: thisismysouth.com

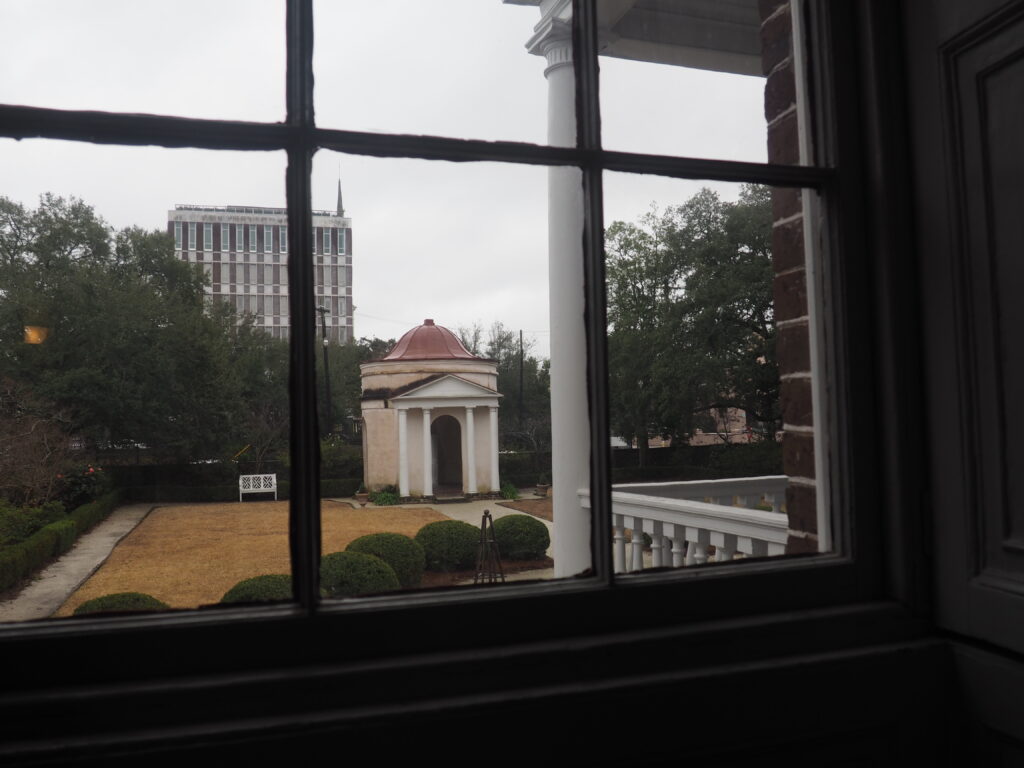

We arrived at the Manigault house in heavy rain and, so, have poached the photo above (duly credited). Manigault was a Huguenot who left France for the usual reasons and established himself as a rice planter with multiple plantations and hundreds of enslaved people inherited from his grandfather. Planters would have a grand house on the plantation as well as one in town. The enslaved people in town were predominantly women due to the type of work required. This was another beautifully restored house, true to the period, typically with original furnishings.

the aiken-rhett house (1820)

The Enslaved Quarters

The Aiken-Rhett House is a preserved, not restored, house, complete with slave quarters which, especially if visited on a rainy day, can be pretty melancholy. “Preserved” means agnostic as to time period and maintained in the same “as found” condition as when taken on by the Historic Charleston Foundation in 1995 after it had been acquired in 1975 by the Charleston Museum directly from the Aikens (who had owned it for 142 years). The Aikens were politicians, slave holders and industrialists; and much of the furnishings and even the painted and papered surfaces have been undisturbed since the 1850s in both the main house and the slave quarters.

The Main House

Among the glories of the house faithfully preserved by the Foundation is the paint in the main reception rooms applied by Wes Craven in 1982 while shooting the horror classic Swamp Thing. Take a close look at the wallpaper to the right of the bust, above. You can see the pins holding small sheets of plastic intended to protect the 19th century wallpaper from further decay. A few more hurricanes and there may be less to see.

The Battery

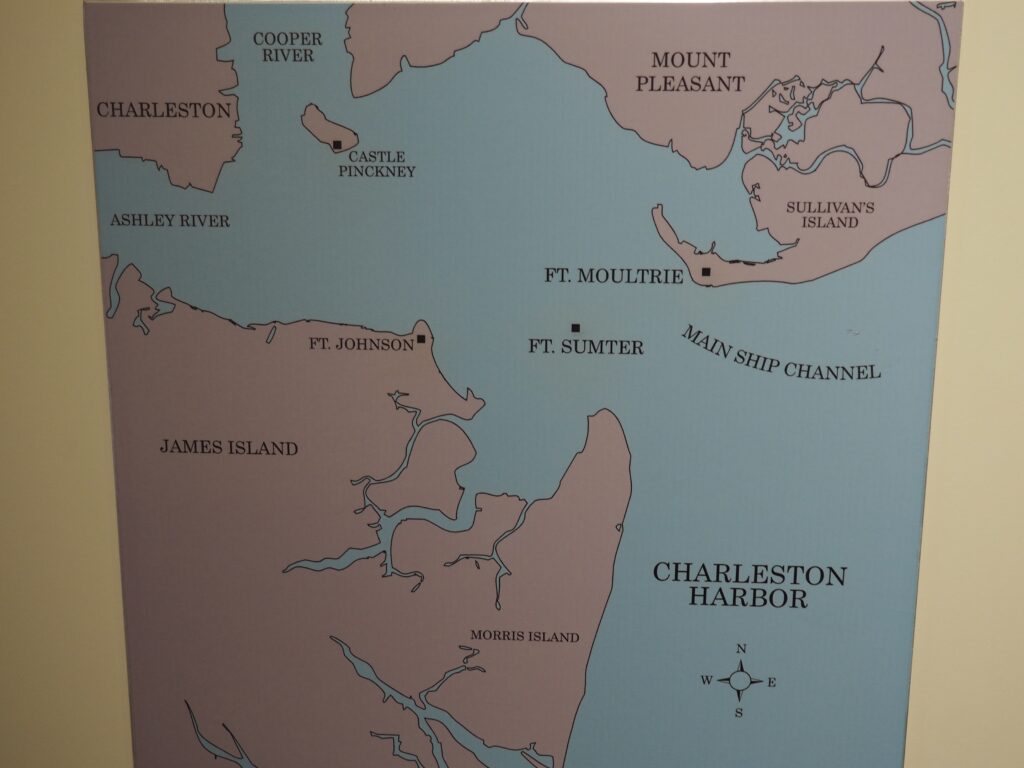

Being granted a sunny day, we walked the Battery neighborhood, along the more southerly stretch of river with a view out to the harbor and Castle Pinckney, where lots of workmen were out repairing and painting the stupendous mansions.

Fort Sumter

Thanks to a break in the windy, stormy weather, the Park Service resumed boat service to Fort Sumter and we were able to make the 11:00 ferry, learning on the way that the “Fort Sumter” we spotted from the Battery was actually Castle Pinckney. It seems that the fort is rather low to the water because it was largely destroyed by the Union when they attempted to take it back from Rebel forces in 1863. The Confederates, of course, fired the first shots of the war from Fort Moultrie in April 1861 and gained the fort due to the Union’s hopeless position. More modern weaponry had made brick forts pretty much obsolete since the fort’s construction after the War of 1812 on a sandbar transformed into a manmade island. Just above the “l” in “Projectile Embedded” you can see what smacked into the back of the fortification from the Federal bombardment. As those lyrics by Francis Scott Key remind us, it’s not only what comes at you from the front that can be deadly (like the shrapnel from those “Bombs bursting in air”).

Old Exchange and Provost Dungeon (1771)

The British finished their Customs House just before the Revolution, so the cellar intended for secure storage housed prisoners of war instead. The building has long been owned and operated by the DAR (Daughters of the American Revolution) who maintain a small museum and run tours of the dungeon. It’s also one of only four buildings still standing where the Declaration of Independence was ratified.

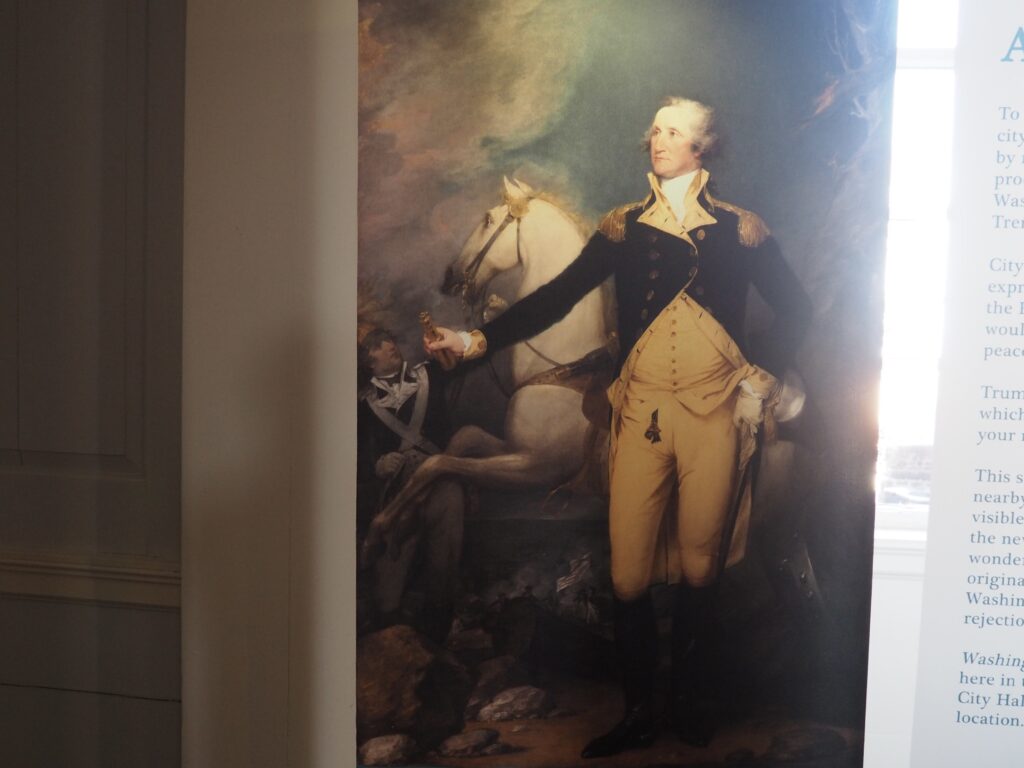

The City of Charleston commissioned John Trumbull to paint a portrait of George Washington to commemorate his visit to the city. He presented the painting on the left, depicting a heroic Washington at the Battle of Trenton. This was rejected by the city because they wanted a depiction of Washington in their city. Trumbull complied, although wags have often wondered if there is a message from Trumbull somewhere in the painting. [For those who can’t quite grasp, and really need to ask: please see the hint below.*]

So, farewell, Charleston. It was a lovely visit to the “Holy City,” a place with too many churches to count.

*The insult is not: “You’re such a horse’s head!”