A Beginning at Chaco

Chaco Culture National Historical Park

Each of the 19 Puebloan tribes, with different languages, traditions and genetics, has stories of what we call Chaco and of their time at Chaco as an important stage along the migratory path taken since their origins in this world from a unique “emerging place.” Some of those traditions speak of a golden age of brotherhood. Others speak of dark times, dread and slavery. What is clear is that from around 700 or earlier, settlement in significant surface dwellings began in Chaco Canyon by various Puebloan peoples, settlement that began modestly and ended with a monumentally complex and ambitious society and the public architecture to go with it. It is also clear that by 1300 all of those peoples had yet again moved on.

We found Chaco down a long, dusty, washboard of a road taking us on gravel and dirt for half of the 1 1/2 hour drive from the nearest place with a motel, Farmington, New Mexico. The only other option is staying at the campground where, thank heavens, they’re finally taking reservations. It was one of our many stops in the Four Corners as we carved a giant loop in and out of Grand Junction, Colorado, to enjoy the area and deepen our understanding of the inheritance of our country. To make some sense of this, we’ll start the telling with Chaco.

Although the area was sparsely populated from roughly 9300 BCE, from around 400 CE the development of pithouses (more on this later) allowed a year-round population to thrive by cultivating corn, squash and beans. By 1200 CE the population of the Four Corners region was greater than it is today. Pueblo Bonito was one of the first Chaco “great houses” and other above ground settlements on which construction began by 850.

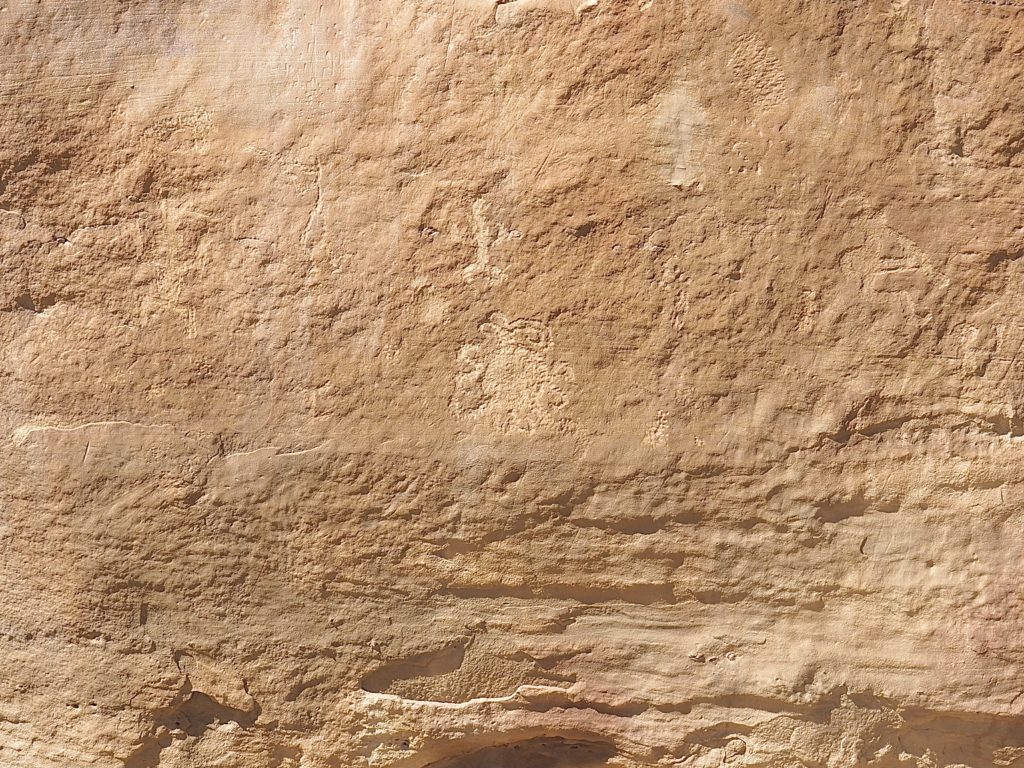

As with most people of the era, the Chacoans were obsessed with the study of the heavens. The sun, moon and stars behaved in orderly and predictable ways that not only inspired humans, but provided invaluable tools by which to organize the timing of agriculture (especially, when it was safe to plant crops). The central figure in the panel, above, is a representation of a total eclipse of the sun and the panel is located at one of the many observation posts the Chacoans used for their observations.

Pueblos have large plazas

An enormous slab from the backing cliff smashed part of the site in the 20th century

Walls were designed to support 3 stories

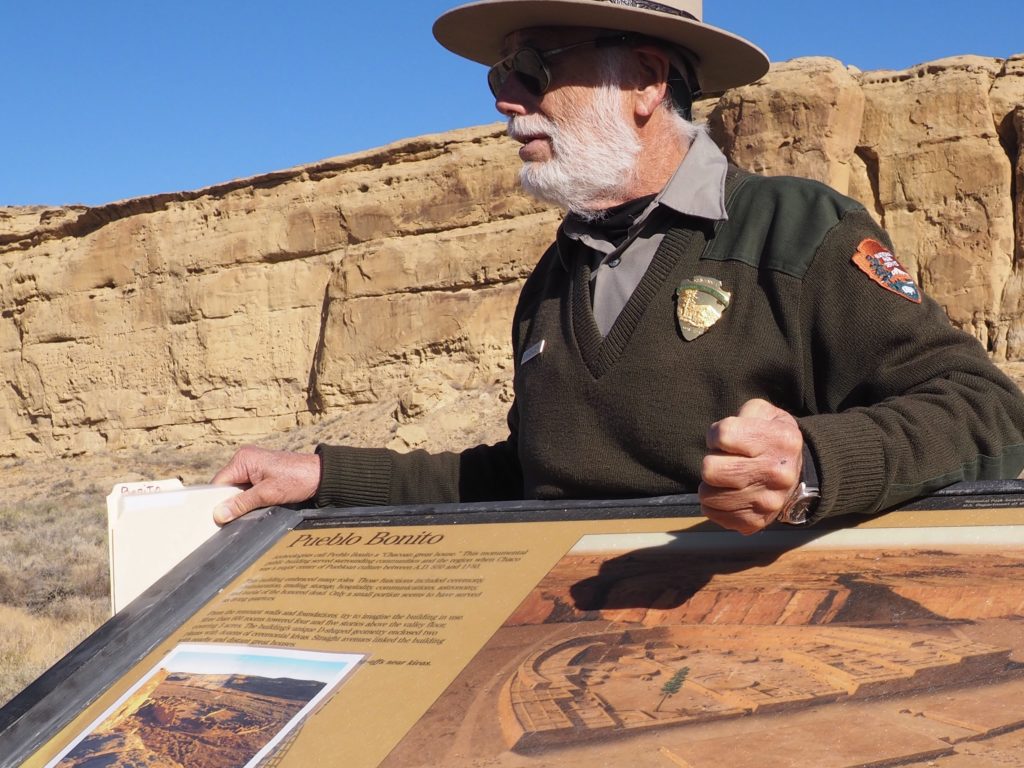

Pueblo Bonito covers a very large area and is one of many settlements at Chaco.

Great Kiva, Casa Rinconada

Great Kiva, Casa Rinconada

Kivas are submerged dwellings with a standard architecture for a small family group and include, for instance, a hearth with a clever ventilation system and post holes for a loom. Great Kivas are public architecture and likely had a ceremonial purpose as a gathering place that could accommodate hundreds of people. This is a living tradition, carried on by contemporary Pueblo people. This Great Kiva at Casa Rinconada is the largest excavated kiva in Chaco Canyon. While other Great Kivas are placed in the plazas of great houses or along roads, this Great Kiva is on a prominent hill set among a large community of villages.

Una Vida is another “great house” at Chaco, i.e. a large multistory public building with a Great Kiva. However, it has undergone only a small amount of excavation so that it looks like it did in the middle of the 19th century when the area was discovered by the modern world. The scattered building material on the ground in the foreground indicates that underneath lies a structure. Archeologists are, however, focused on stabilizing structures and trying to prevent damage rather than further ambitious excavation. Lidar is now used to locate structures and improve our understanding of what lies beneath the surface.

Moving on from Chaco

(or maybe that’s too simple an explanation?)

Aztec Ruins National Monument

The unfortunately named Aztec Ruins lie about 70 current road miles north of Chaco Canyon. The dwellings and other structures there are, of course, not Aztec and calling them “ruins” offends the Pueblo who consider them to be current sacred dwellings. This substantial settlement is part of the same culture as Chaco and it is one of perhaps 150 great houses over a region of as much as 60,000 square miles connected by 30 foot wide engineered road beds, 400 miles of which have been documented.

Around 1100 C.E., Ancestral Puebloan people from Chaco migrated north and began construction at Aztec Ruins, an existing settlement known as the Place by Flowing Waters (the Animas River). Rather than the old term Anasazi, these master builders are now referred to as the ancestral Puebloans to make clear that they were the ancestors of the various Pueblo peoples and not a distinct tribe.

Detail showing construction of pillar with masonry and crisscrossed rows of poles

Central fire pit, entrance in roof of Great Kiva and ancillary pits (for foot drums?)

15 surface rooms surrounding the Great Kiva are unique to this particular structure.

Excavated by Earl Morris (a fedora hat wearing inspiration for Indiana Jones) in 1921 and reconstructed by him in 1934. Surviving remnants of plaster guided the color scheme.

Even for 5’ tall Puebloans, the doorways were tight.

T-shaped doors normally faced plazas or balconies.

Rooms interconnected from front to back of the building, not side to side.

Willow mat sewn together with yucca cord, more than 800 years old closed off this opening.

Walls were thick to support multistory buildings.

These 900 year old spruce, Douglas fir or ponderosa pine original roof beams are as large as telephone poles and were transported over long distances. Over them are aspen or pine cross beams which are topped by a layer of juniper splints on top of which tamped mud formed the floor above. Morris “borrowed” some of the roof beams for his own home which now serves as the visitor center for the Aztec Ruins National Monument.

Mesa Verde National Park

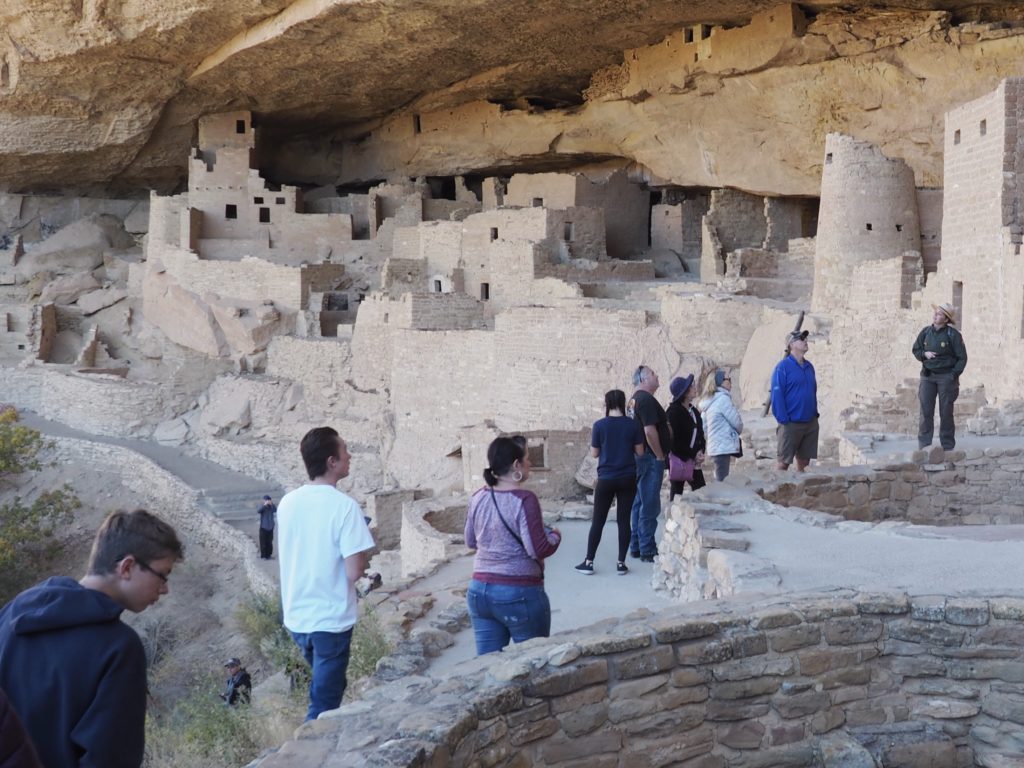

It may look like a theme park attraction, but this is a dwelling reconstructed from the ruins of a structure built between 1190 and 1260 CE by those ancestral Puebloans down below the rim of a canyon, part of a 700 year occupation begun around 600 of what is now Mesa Verde National Park. It’s the largest cliff dwelling in North America and it can be visited in the company of a Park Ranger.

Access is not for the faint of heart.

And is strictly controlled.

Fortunately, we were not required to use the same hand and foot holds as the Mesa Verdeans.

In the back of the cave, a “seep” provided water for the inhabitants.

Part of the original plaster

Unlike Chaco Canyon and Aztec Ruins, the dwellings at Mesa Verde are nestled in cliffs. And, there are thousands of them throughout the region. Ancient dwellings are not restricted to our national park system. The cliff dwellings at Mesa Verde were built by people farming on the mesa – corn, beans & squash, of course. Why they chose to build there no one can say for certain. It’s all informed speculation as they did not have a writing system with which to communicate with the future.

It may not be photogenic, but this pithouse is an important part of the ancestral Puebloan story. It was roofed with an entry through the roof, as in the later-developed kiva structure. It had many of the kiva attributes, including a ventilated hearth and posts for a loom. In population centers as they developed into the stage of the cliff houses or great houses, it’s likely that most people still lived in pithouses. A typical pithouse is thought to have accommodated a nuclear family.

Oak Tree House, Mesa Verde

New Fire House, Mesa Verde

Hemenway House, Mesa Verde

Spruce Tree House, Mesa Verde

Mary Hemenway was a 19th Century Boston philanthropist who funded the first scientific archeological study in the Southwest, including of Mesa Verde. From our familiarity with Hemenway Landing in Eastham, we knew It must be a family with ties to our hometown.

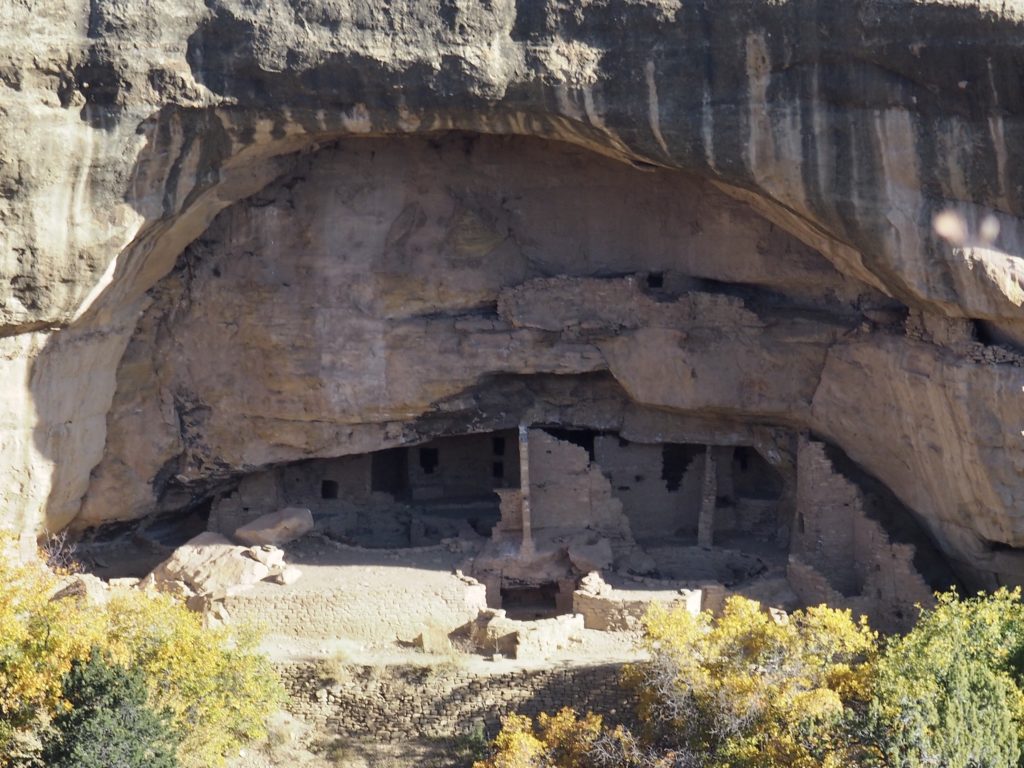

In our visit to the Four Corners region, we discovered that cliff dwellings are everywhere, there are thousands of them of different shapes and sizes wedged into large and small openings up and down the canyons. Sometimes it seems that people accessed them from the mesa tops and sometimes from the canyon bottom or in some places both. It’s usually assumed that the Puebloans built there for defensive purposes, although that’s not a very satisfying explanation. Other perfectly good reasons would seem to be ready access to water when it’s seeping out of the canyon walls in the back of the openings, the moderating effect on temperature from living in a cave, and the thrill of accomplishment. After all, the people building the cliff dwellings did so on the backs of the significant accomplishments at Chaco.

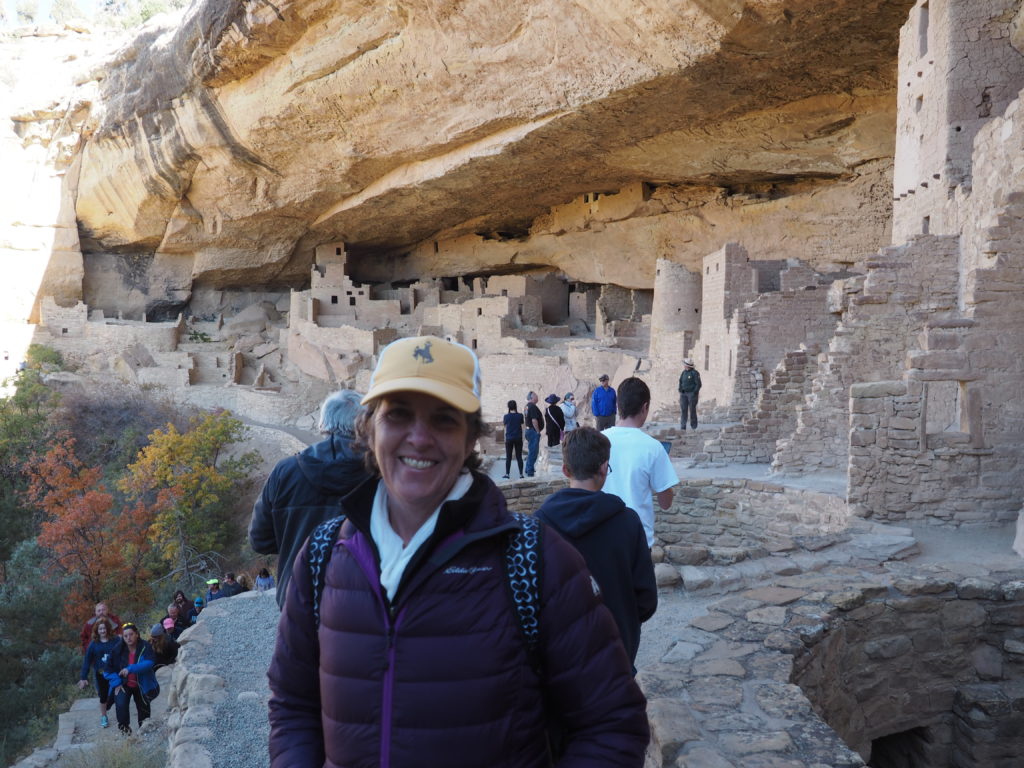

Out of Cliff Palace, Mesa Verde

The intrepid photographer poses for a picture.

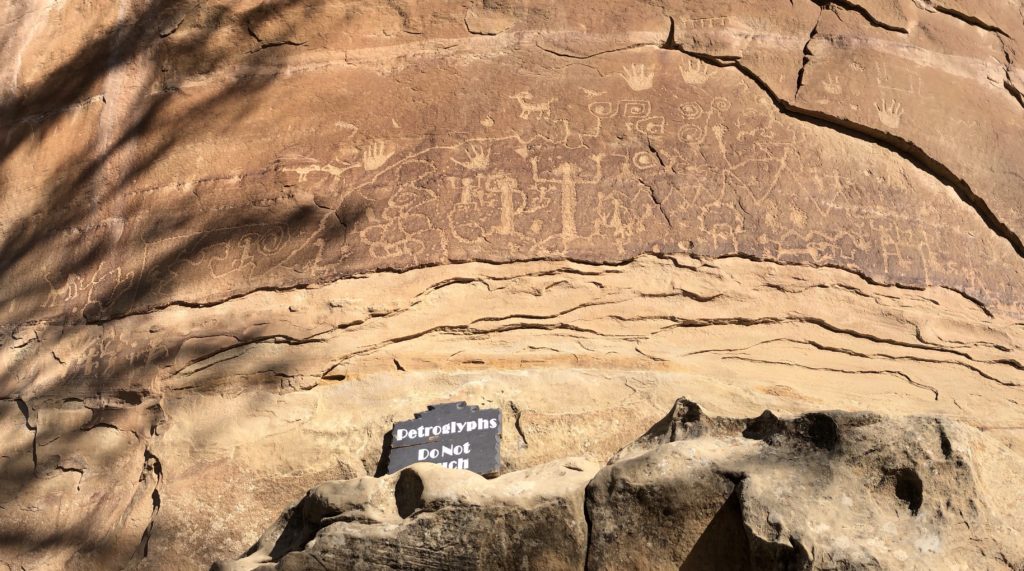

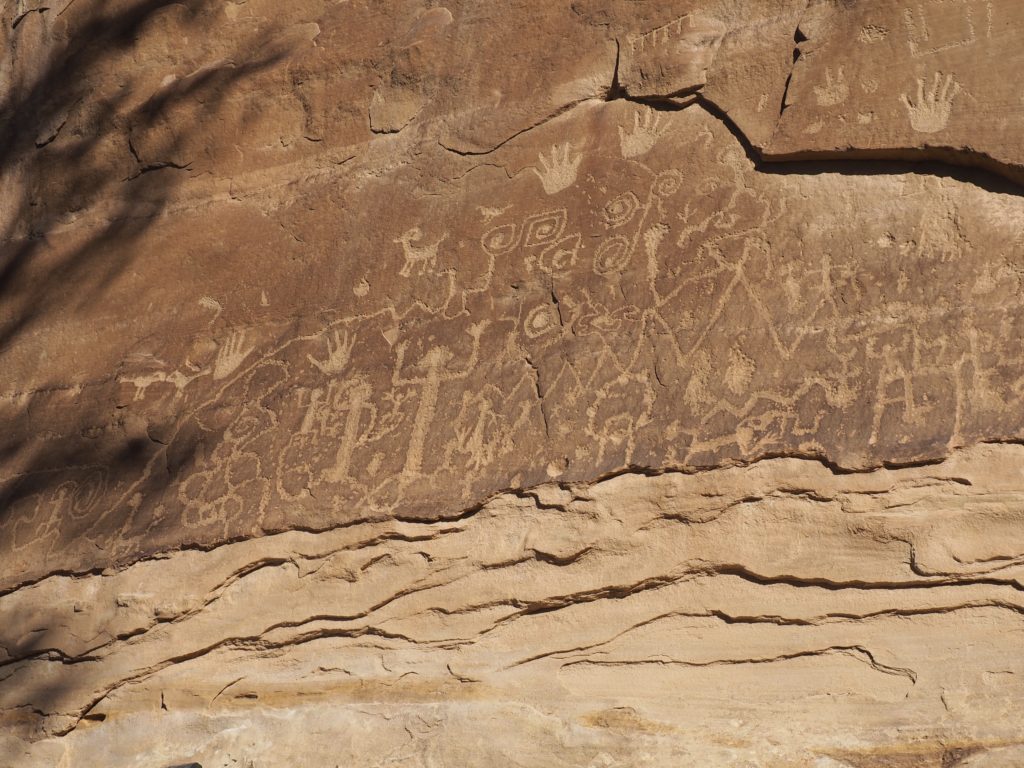

In 1942, four Hopi men interpreted the petroglyphs. The square spiral connected to the spiral to its left represents Sipapu, the place at which the Pueblo people emerged from the earth (the Grand Canyon).

Canyon of the Ancients National Monument

Lowry Pueblo, Canyon of the Ancients National Monument.

Great Kiva, Lowry Pueblo, Canyon of the Ancients National Monument.

Great Kiva with Lowry Pueblo in background

Cooking pot found on what’s now the Ute Reservation. Circa 930-1170.

Two birds chasing a lizard. Found on a kiva floor on Mockingbird Mesa. Circa 975-1150.

Canyon of the Ancients National Monument is run by the Bureau of Land Management and they do a nice job. Their museum is small, but well thought through and helpful and they have some good introductory films, including one about the Wetherill family who were ranchers who conducted their own archeology in the 19th century in a careful and respectful way, recognizing that they had stumbled on something special and had a responsibility to protect it.

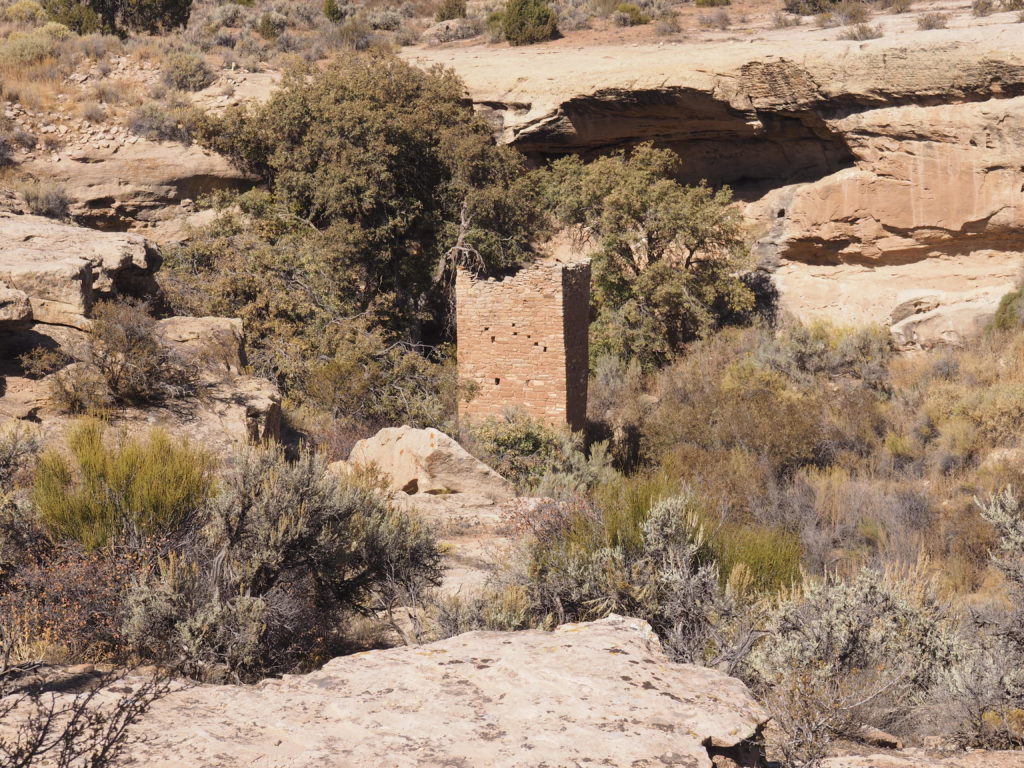

Hovenweep National Monument

Yes, that’s a dwelling built on a boulder.

At Hovenweep (Ute/Paiute for “deserted valley”) dwellings are on the canyon rim, the canyon floor, and on the canyon walls of this relatively small and shallow, almost intimate, canyon and no one has lived there for over 700 years. Again, was it drought or the depletion of resources in this desert environment? While the area had long been populated, a great influx began around 1100 and by the late 1200s everyone was gone. Perhaps a newly fashionable area was ruined by its success.

Canyon de Chelly National Monument

Canyon de Chelly

With our Navajo guide, Eleanor Yoe

In the canyon

Canyon de Chelly is the intersection of different histories, some of which don’t actually intersect. The Ancestral Puebloans, the Hopi and the Navajo have all left their marks, although by the time the Navajo arrived, the Ancestral Puebloans (or Anasazi to the Navajo) were long gone. There had been conflict over the canyon and the Navajo now control it along with the National Park Service. There are many cliff dwellings in the canyon which the Navajo treat with respect as still containing the spirit of those who have departed. There are also a startling number of pictographs and petroglyphs. So, the Navajo now guide the outside world through their land to see artifacts of another time while they continue to live there with small scale farming and livestock. Mostly, it has become a summer residence for all except one woman who lives in the canyon year round. It’s a place to enjoy the traditional life. The ride out and back, by the way, makes Toad’s Wild Ride seem incredibly tame, as you careen through loose sand and plunge in and out of steep gullies, grateful that it’s not the wet season when they’re running with water for two months.

Of course, hogans are always round and the doorway always faces east. It’s the external structure to support the roof of this old stone hogan that is square. The Navajo moved into Canyon de Chelly around 1500 and it is an important home for them. While the federal government did establish a National Monument, the land is Navajo owned and about 80 families have rights on the land. Being a matriarchal society, land passes to and is owned by women. Our guide Eleanor’s great grandmother had owned land in the canyon and she has many friends there. As part of her business, she sets up campsites for non-Navajo people and provides Navajo guides (which are required at all times in order to be in the canyon). In addition to the occasional cow, small groups of mustangs (some branded, some wild), and the usual small animals, the canyon boasts bobcats, mountain lions and bears.

Spider Rock, an 800 foot sandstone spire, is an important part of Navajo tradition. The Spider Woman lives there. She brought the knowledge of the loom to women and is the great protector of humans, except for misbehaving children, that is. Naughty children she will capture with her giant web and eat. A double edged story if we’ve ever heard one. Eleanor likes to camp out by Spider Rock. That’s where we ate lunch.

Sigh . . .

more

cliff

dwellings!

Sigh . . .

more

rock

art!

All the cliff dwellings and rock art can become overwhelming after a while. It’s like the fatigue you can feel when visiting one of the great art museums of the world. You know that each of these things you’re trying to take in and understand and give its due is not being adequately appreciated because you only have so much capacity for wonderment at one go.

That made our time with Eleanor, hearing her stories about people, accidents, bear and mountain lion attacks on livestock, the destruction caused by invasive Russian olive and tamarisk, morning prayer with corn pollen, the work she does to maintain the rough track through the canyon, the somehow sad beauty of the cottonwoods turning yellow when they really don’t belong in the canyon (having been planted by the CCC to try to stem erosion) a wonderful balance. We already knew about the atrocity at Massacre Cave, the refuge sought by the Navajo at Fortress Rock and other intersections in the lives of people in the region that we’d like to forget, but mustn’t. It was just nice to hear about ordinary people living ordinary lives while we admired the work of people who had lived in the canyon long before our time.