Month: March 2015

Weirdly Wonderful

Kabuki! Men dressed in elaborate kimonos with extravagant makeup. Musicians playing the shamisen, flutes, drums, and an assortment of other instruments. Singers with a sound like cante flamenco, bending their tone in and out of tune. Extravantly stylized, but exquisitely expressive, acting and mime. Speaking voices modulated to an extreme, so much so that the limits of the human throat seem to be approached. Fable-like story lines. These are the elements of Kabuki and they are strangely compelling when all put together.

So, the four of us ventured into Kyoto to see it live and with good seats. As the time for the performance approached, the atmosphere became more surreal as uniformed young women intoning a warning chant-like against the use of photography or recording devices worked their way up the aisles, as a wood block sounded seemingly at random.

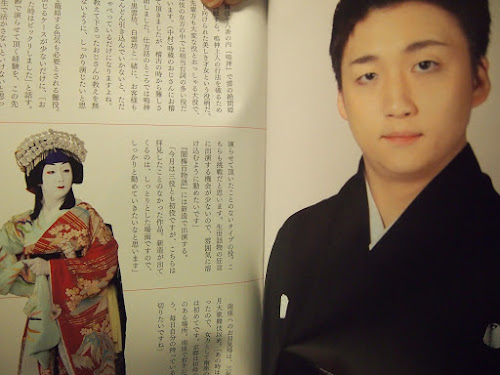

We were able to follow the stories reasonably well thanks to plot synopses in a booklet with the bios of all the actors, including this gentlemen who played a young woman who succeeded in outwitting the hermit so the dragon could be unleashed and the drought brought to an end, or something like that.

Back in Japan

We’re back in Japan to visit Kyle & Ai.

Since it was a work day for Ai, we headed into Kyoto with Kyle for a tour of the Imperial Palace.

Even though it was a brisk day in Kyoto, we learned there were another 9 1/2 inches of snow back home. It was here in Kyoto that Shogun Tokugawa turned over power to Emperor Meiji in 1868, ending Kyoto’s 1,000 years as the capital of Japan when the Emperor moved his capital to Tokyo.

The main ceremonial building of the palace complex is the Shishinden, where enthronement ceremonies took place. When Emperor Akihito acceded to the throne in 1989, the Imperial thrones were flown by helicopter to the Imperial Palace in Tokyo.

The feet of the Emperor at Kyoto never touched the ground. The Seiryoden was the Emperor’s residence. He would sit on raised tatamis to receive people and retreat to the tent behind when he tired. If he left the building he would be carried.

Of the 1,800 paintings in the Palace, these are a few of the very few that can be seen by the public. They adorn waiting rooms for aristocrats seeking audiences with the Emperor. The lowest order of nobles were assigned to the room decorated with blossomin cherry trees and with red tapes between the tatami mats. The next highest group used the room with cranes and white tapes between the tatamis. The very highest of the nobles waited in the room with white tapes and tigers on the walls. In its adoption by the Japanese, the zodiac retained the tiger even though the only sign of tigers ever having lived in Japan are the fossil remains of prehistoric times. However, the tiger has always been a potent symbol of bravery, dignity and the power to protect.

The Oikeniwa Garden, inside the palace walls, provided a moment of traquil reflection . . .