Like every big city, Boston has layers – layers of history and architecture and how we use and enjoy what the city has to offer us. In Boston, those layers include new layers of the land itself, as the city filled in portions of marsh and bay and riverfront to dramatically expand the colonial era city.

We thought seeing Boston from the water would provide an interesting perspective, so we joined an architecture tour by boat.

(aka 200 Clarendon)

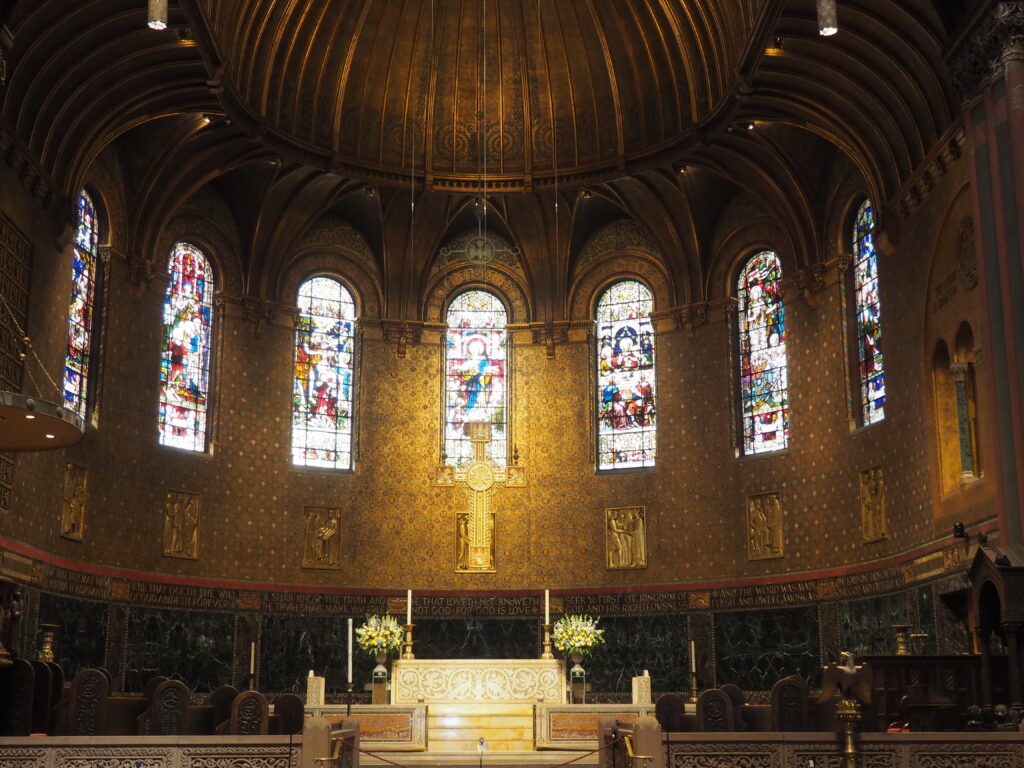

Trinity Church at Copley Square

After traipsing through countless churches and cathedrals, we had pretty much sworn off them as sites of interest. What piqued our interest in Trinity Church was curiosity about its story, or rather, it’s stories. First, the church was built in what’s known as the Back Bay, a large neighborhood in the middle of the city in what used to be . . . (you guessed it – marsh). So, the church is built on thousands of pilings pounded into fill. Then, it is widely considered to be one of the most significant buildings in America. It was the first major project of the architect H.H. Richardson and a sort of master template of an architectural style known as Richardsonian Romanesque that was imitated all over late nineteenth century America in schools, churches, hotels, and town halls. The church was built under the leadership of its Rector, Phillips Brooks, a larger than life personality. Brooks was considered the greatest American preacher of the 19th century (with some of his sermons remaining in use), preached to Queen Victoria at her invitation and wrote the lyrics for “O Little Town of Bethlehem” (while in Philadelphia). The church is in the form of a Greek cross, providing the sense of a large inclusive space for worship, and is a statement of its times in the interior decoration, as well.

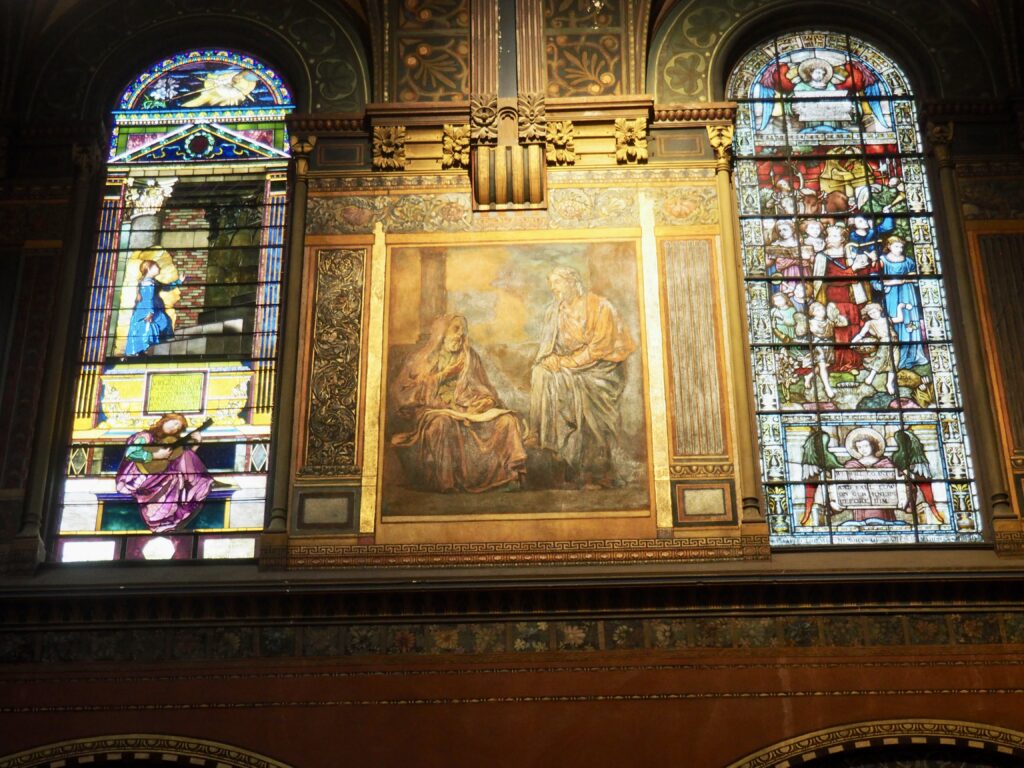

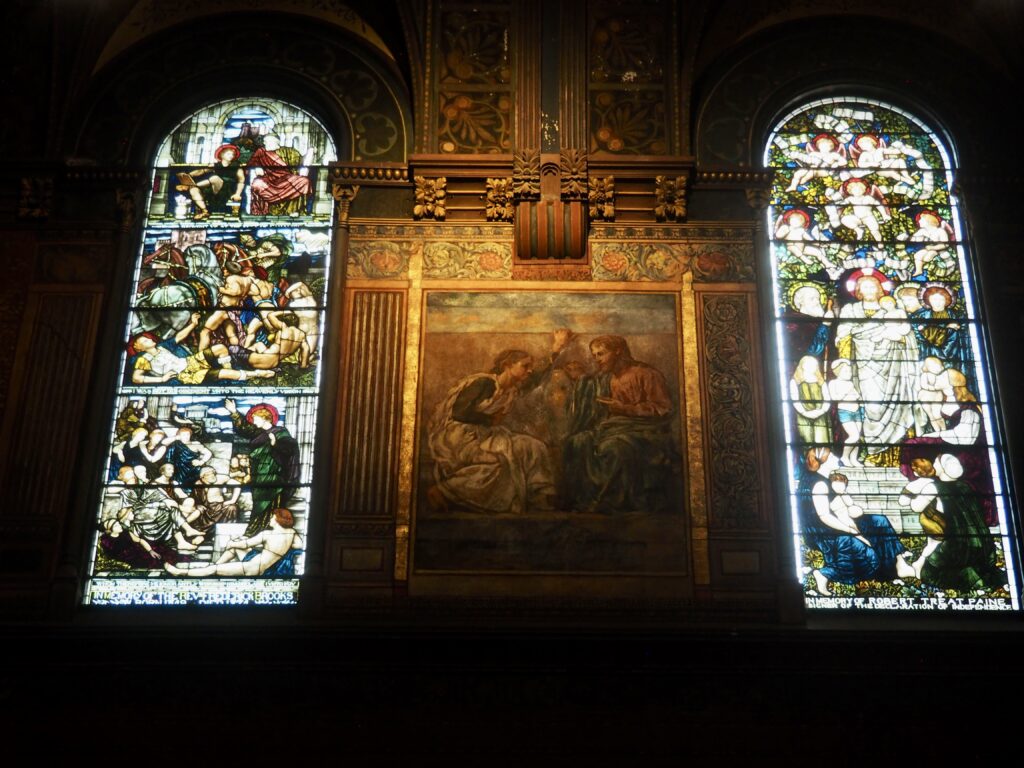

The interior design of the church was entrusted to John La Farge, a painter and innovative artisan in stained glass who incorporated half globes and other three dimensional glass surfaces to gather and direct light, as well as combinations of opalescent and clear glass to create compelling images. He and Louis Comfort Tiffany were great rivals (Tiffany’s windows for Arlington Street Church, below). Trinity is filled with exemplary stained glass by various designers:

Arlington Street Church

Meanwhile, several blocks away, in the first public building to be constructed in Back Bay by another well-established congregation (1729) that had birthed Unitarianism, the Arlington Street Church is host to a sanctuary lighted by only Tiffany windows (a sampling):

Public Garden

Metropolitan Water Works

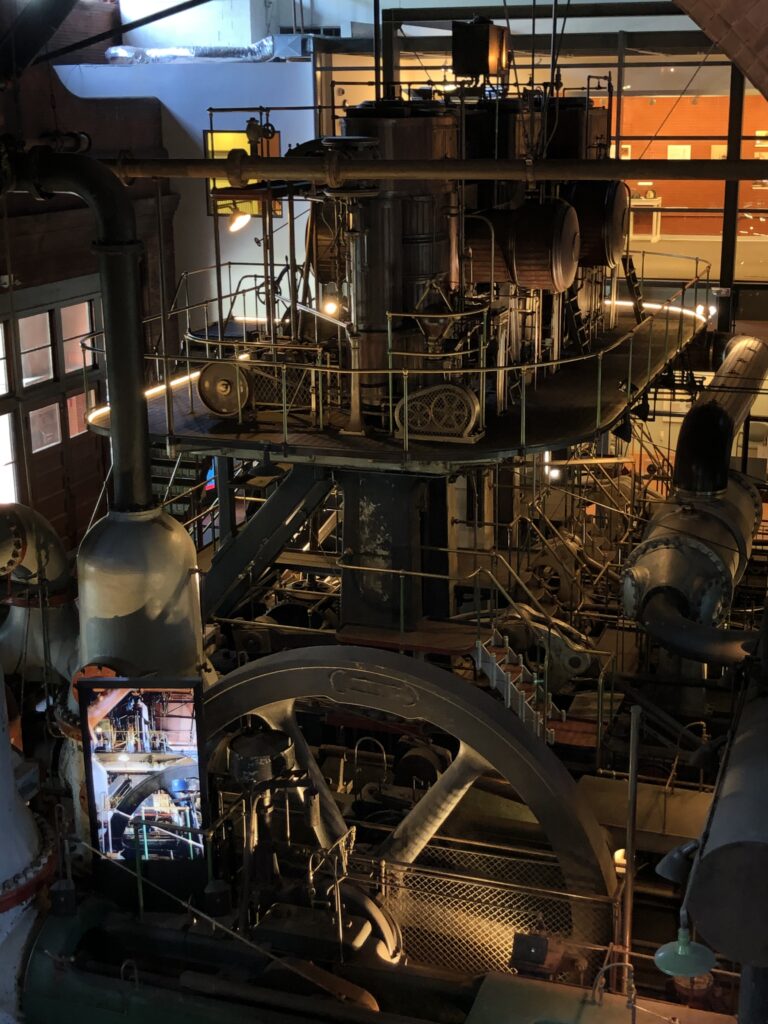

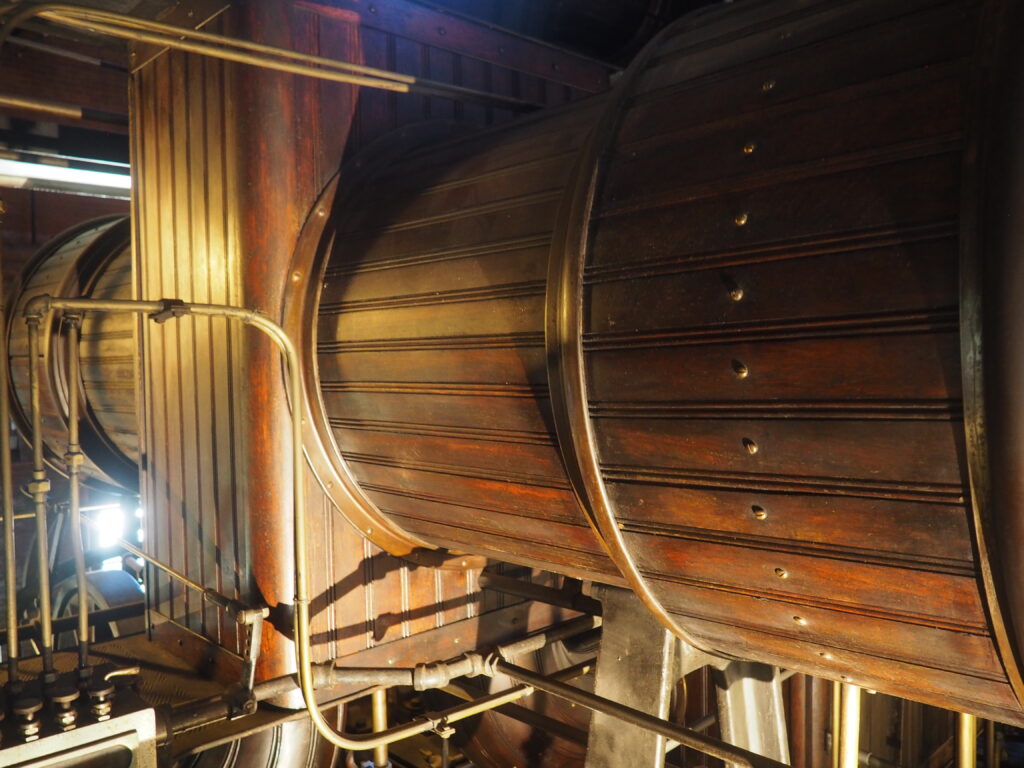

We have a weakness for the beauty of mechanical things, especially displays of 19th century industrial muscle. The Metropolitan Waterworks is now a museum with guided tours of three different stages of technology for getting water pumped from a reservoir to the thirsty citizens of Boston. It was fun climbing through and walking the catwalks, although Jim demurred when it came to the highest level!