More than just awe inspiring structures set on a desolate plain, Egyptian pyramids are deeply religious statements about death and a belief in resurrection and an afterlife. Tombs were always on the west bank of the Nile because that’s where the afterworld could be found and entrances always faced north so that their owners’ Ka (spirit) could more easily find their physical remains and the grave goods left to support and sustain them. But, enough of that for now.

Saqqara

The first true pyramid was designed by one of the geniuses of the ancient world, Imhotep, in the 27th century BC. (He was the chief minister of King Djoser, as well as an architect, physician, judge, and high priest of Ra (the Sun God), and was ultimately deified as a god of medicine and healing 2,000 years after his death.)

(those are not wooden logs)

Imhotep introduced the construction of tombs out of stone, rather than organic materials such as reed, wood and mud brick. He then fashioned the stone to mimic some of these materials. But, his biggest claim to fame was successfully building the first true pyramid.

Some pyramids haven’t held up as well as others, given compromises that were sometimes made in their construction. However, their subterranean parts may have fared better.

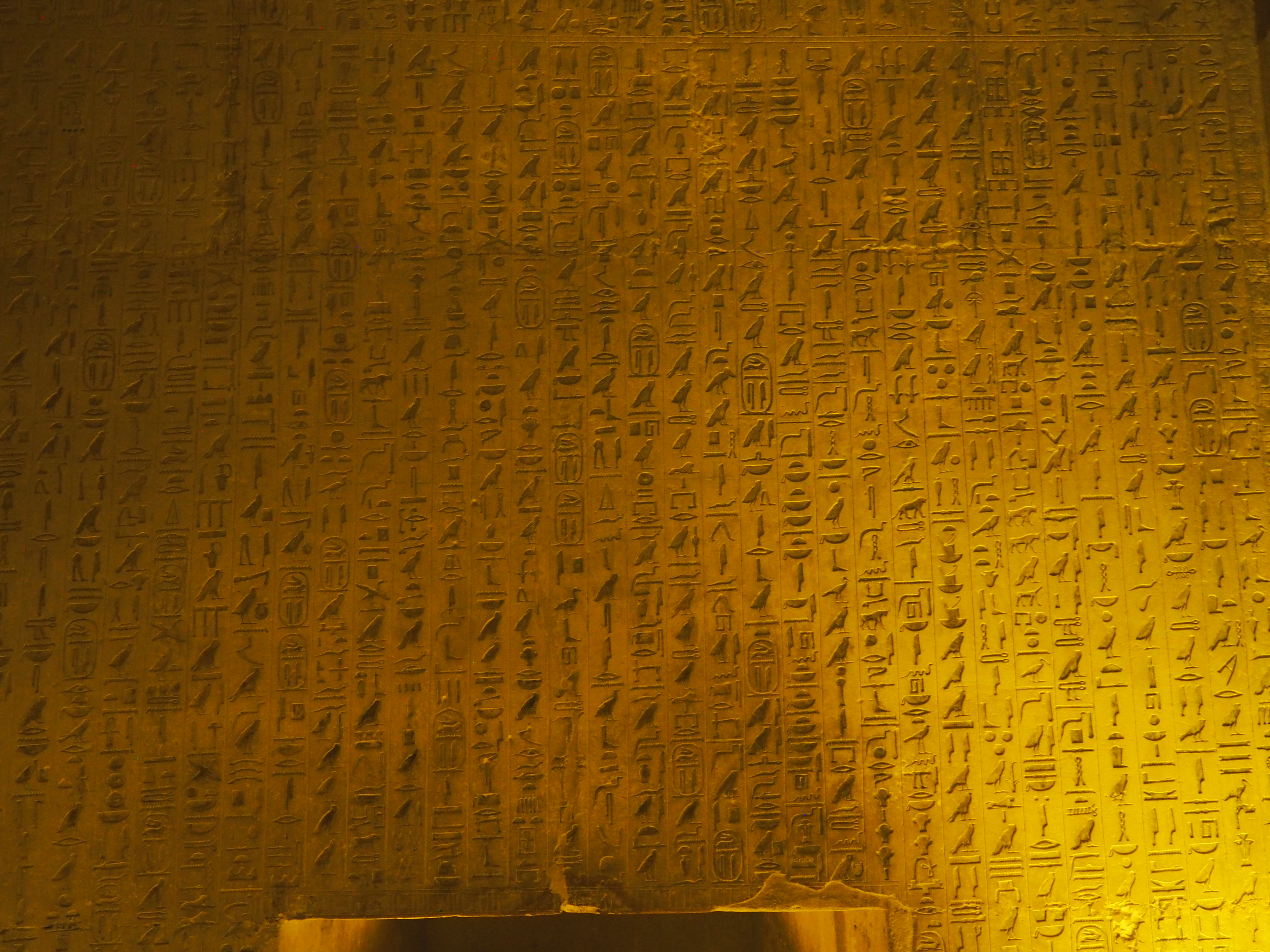

Our university trained Egyptologist was not permitted to guide in the tomb of Unas beneath his pyramid because of concerns about moisture and light adversely affecting the preservation of the tomb writings. However, as was often the case, a local with a flashlight stationed himself within the inner chamber and provided his own version of history in the hope of receiving tips.

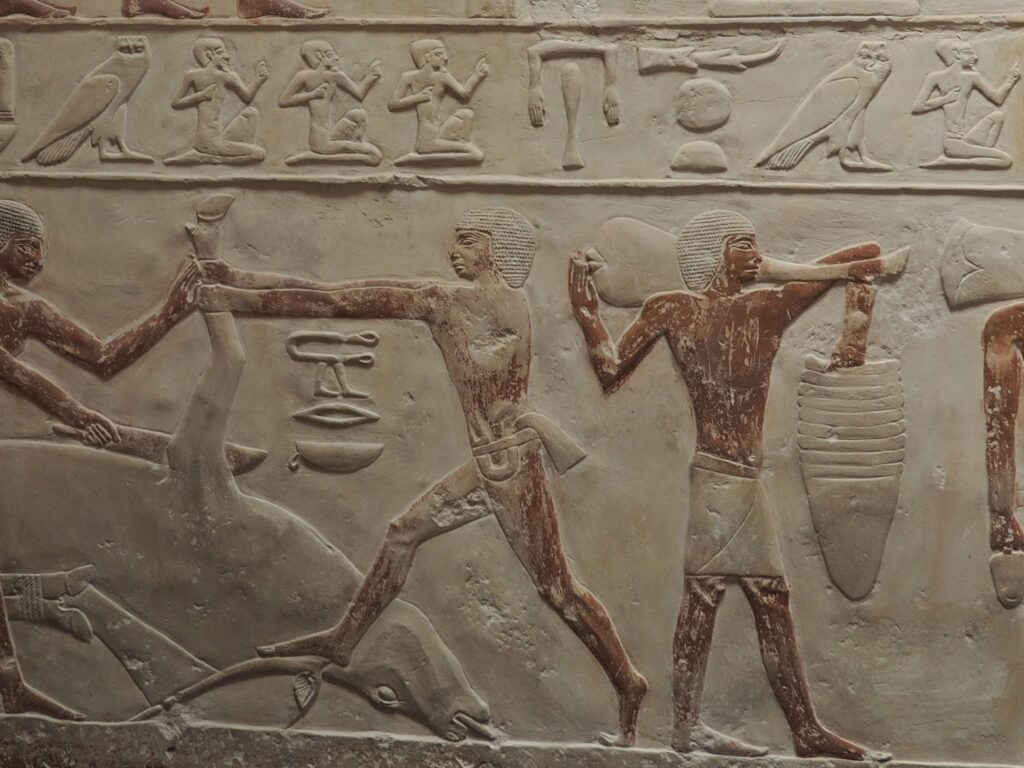

The interior of the mastaba of Princess Idut was somewhat better controlled, although it was shoulder to shoulder in narrow passageways. When she went before him into death, her bereaved father (King Teti(?)) had her tomb decorated with what she enjoyed most in life, including a good haunch of meat.

Giza Plateau

(and young man retrieving two runaway camels)

It’s a big place, Giza, and it’s almost impossible to convey just how massive the great pyramids actually are since we experience them from the respectful distance of a photograph that’s able to contain them. But, do try to imagine them still clad as they were in gleaming white stone (before all the pillaging over thousands of years for construction materials).

(just right of center at the horizon).

Giza is a large and complicated city for the dead, far more than simply three big pyramids looming over the scene. Each of the pyramids has a whole complex associated with it, including a causeway and a harbor to receive materials and, of course, the deceased Pharoah from a canal paralleling the Nile. A very important part of that complex is the mortuary temple where the body of the deceased was prepared. In addition to the big three, there are other smaller pyramids at Giza. There are also many many mastabas, some very substantial, in crowded rows all around the plateau under which those close to the Pharoahs were interred with the same care for the proper handling of the body, proper furnishing with what will be needed for the afterlife, and proper tributes and guidance adorning every available surface.

Not to be outdone by the greater size of his father’s pyramid, Khafre added the now familiar great sphinx in front of his own complex by having a very large rock carved to his specifications. Khufu, of course, built the first and largest of the three large pyramids, having watched his own father (Sneferu) build three “normal” sized ones. Menkaure was the grandson of Khufu. The Pharoahs then seem to have gotten pyramid building out of their systems.